Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Wheat Support Price: A Note For Policy Makers

Wheat Support Price: A Note for Policy-makers

Abdul Jalil, Professor of Economics, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.*

Fahd Zulfiqar, Lecturer, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

Muhammad Aqeel Anwar, Lecturer, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

Nasir Iqbal, Associate Professor, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

Saud Ahmed Khan, Assistant Professor, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

| Wheat Crisis: A Market-based Solution The main recommendation has been for a while and remains true that the government should withdraw from the market. This would mean: (i) start by setting indicative pricing and stand back from procurement; (ii) withdraw from storage over a period of 5 years as private capacity develops; (iii) over a period of 5 years, in a stepwise fashion, withdraw import and export controls; (iv) liberalize spot markets to allow entry and competition through dissolving DC led markets; & (v) develop rules and standards for commodity (forward and futures) markets in key areas as storage develops. This will mean strengthening the Karachi exchange or develop rules for local exchanges. The government can solve this issue through proactive market development policies. However, the time has come to withdraw from the system of government involvement in procurement and prices. It has led to repeated shortages and excesses as well as fiscal costs. The international market can readily supply wheat at short notice. With the market in place, the probability of a shortage will be minimal. Like every other county, the government will monitor and remain ready to intervene in extreme circumstances. Nadeem Ul Haque |

BACKGROUND

Wheat is one of the most strategic crops globally, which has always been a big challenge for many governments. Over the last few months, Pakistan’s government is struggling to fix wheat prices in the country due to weak governance and mismanagement. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) for the Year 2019-20 was PKR. 1,400, but the market price of wheat rose to PKR. 2,256 per 40 kg in the first week of October. The Prime Minister of Pakistan directed relevant authorities to devise a comprehensive plan to ensure the supply of wheat on market prices. The plan should look at the current stock, future demand, and import policy to fulfill domestic needs. PIDE has developed a brief to provide a comprehensive plan to ensure the supply of wheat on market prices.

___________________________

Acknowledgement: We are thankful to Vice Chancellor PIDE for guidance and support to finalise policy note. We are also thankful to Ms. Ramla Zubair (Intern, PIDE) and Mr. Muhammad Shehriyar Khalid (Research Assistant, PIDE) for their assistance.

WHEAT PRODUCTION AND SHORTFALL

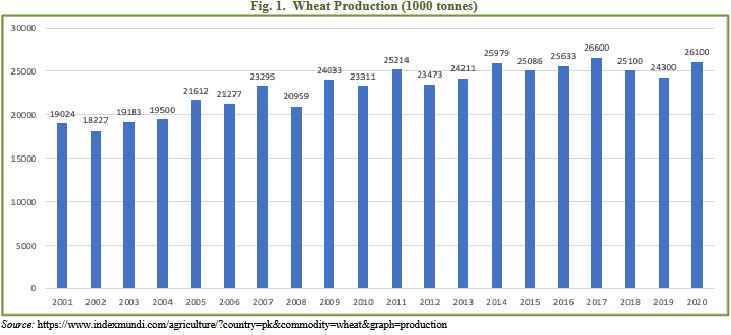

Wheat is one of the most strategic crops globally, which has always been a big challenge for many governments. Over the last few months, Pakistan’s government is struggling to fix wheat prices in the country due to weak governance and mismanagement. The current year’s wheat production is 25.5 million tonnes (1.2-million-tonne increase over the previous year), against the targets of 27 million tonnes (Figure 1).

The estimated shortfall was 1.5 million tonnes. Pakistan procured 6.5 million tonnes of wheat from this year’s harvest, about 80% of its goal. Around 60% of total wheat production is retained on farms for the village and household food consumption and seed. While the government procures approximately 20-25%, the remaining 20% is available in the open market for sale/purchase. So, the government is the dominant player in the wheat market, determining prices, supply, and storage.

No import or export of wheat is allowed. During crisis (shortfall or excess supply), the government provides an exemption to trade wheat internationally. To fulfill the country’s current demand, the Government of Pakistan allowed importing wheat on a subsidies basis. Pakistan’s government has lifted 60% regulatory duty, 11% customs duty, 6% withholding tax, and 17% sales tax to incentivize wheat import in Pakistan. Still, things did not go as planned, and the government could not avoid the price hike.

DETERMINATION OF WHEAT SUPPORT PRICE

To ensure a smooth supply of wheat and incentivize farmers to produce more, the Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation (PASSCO) procures wheat on a Minimum Support Price (MSP). This price is determined based on the excess and shortage of wheat supply in Pakistan. Through the MSP, farmers will receive a fair amount of price for their upcoming crops to invest in agricultural commodities production.

The Ministry of National Food Security and Research suggested that wheat’s support price should be increased to motivate farmers to increase wheat production in the future. The Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) consulted Ministers and Special aides to conclude whether the support price should be increased by 25%, i.e., from PKR1400 per 40 kg to PKR1745.

MSP Determination in India: The India Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare recommends MSP for India’s major agricultural commodities. CACP operates as a statutory body that prepares and submits reports about the pricing of products for Kharif and Rabi seasons and recommends MSP to the State and Central Governments. The State Governments submit reports to the Central Government, which takes the final decision after considering the supply/demand situation of the agricultural produce. Indian government only buys as much as 25 percent of the grain produced in the country at the rate of MSP, while the rest of the remaining crop (75 percent) is sold at the market price. Only 6% of the Indian farmers reap this policy’s benefit as 94% are landless farmers. The Government of India has a mechanism in place, and CACP recommends MSP for India’s major agricultural commodities.

COST OF PRODUCTION AND PRODUCTIVITY

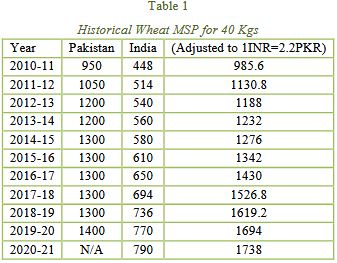

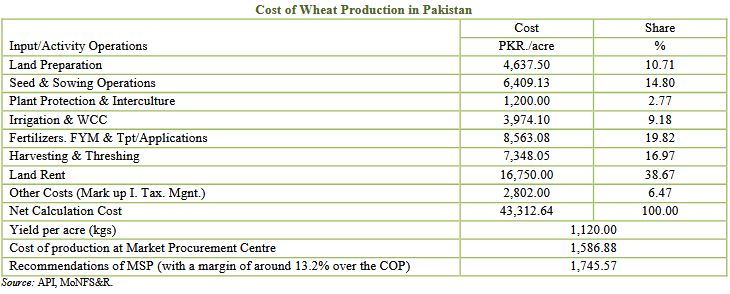

The cost of cultivation (PKR. 43,312 in Pakistan) is more than double in Pakistan than in India (PKR. 16,117). At the same time, the production is 56% less in Pakistan than in India. So, it is essential to rationalize the inputs and invest more heavily in cross-cutting seeds and land preparation technology. Over the last five years, Indian MSP is increasing, and production cost nearly remains the same, considering its strong currency, whereas, in Pakistan, MSP is relatively decreasing.

Learning from Indian Experience: India has a well-established system to govern MSP and procure wheat. Pakistan can develop such a system to monitor prices regularly. Yet, the Indian system is skewed and gives benefits only to 6% of the farmers. Similarly, in Pakistan, MSP only offers benefits to less than 5% of big landholders. In comparison, the remaining 95% of farmers either do not sell wheat or even sell at low prices (exploited by middleman due to corruption and rent-seeking).

IMPACT OF NEW SUPPORT PRICE ON INFLATION

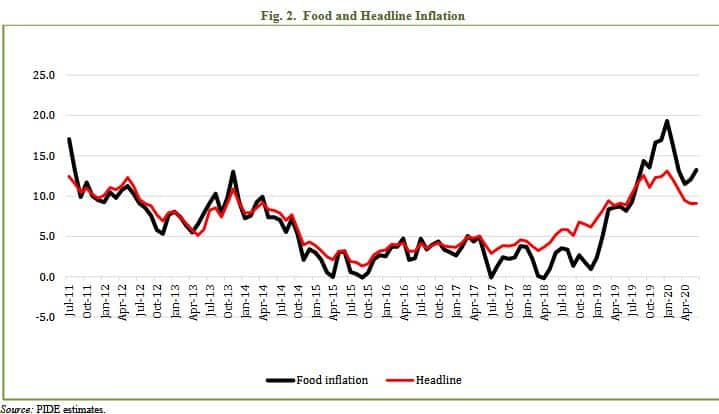

Food prices are rising fast in recent months, posing a possible threat to the poor’s livelihood. Furthermore, food inflation remains the major contributor to the various inflation episodes over the last ten years (Figure 2).

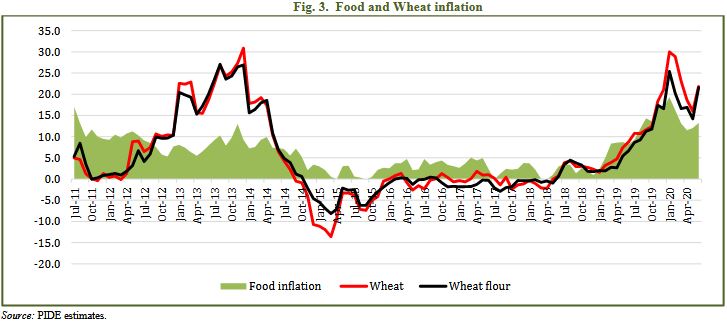

The wheat and wheat flour remain the primary drivers of the recent episode of food inflation. Notably, wheat inflation was deriving food inflation in most cases (Figure 3) over the last ten years. Recently, the government is going to announce an increase in the MSP of wheat. It is essential to review the inflationary consequences of any price change in the wheat. This brief aims to evaluate the impact of an increase in MSP on average inflation.

We find a low correlation between MSP and food inflation as compared to retail wheat prices. More interestingly, retail wheat inflation was even negative in 2014 and 2015 when the government increased MSP from PKR. 1,200 to PKR.1,300. Furthermore, the retail wheat price is much higher than MSP; therefore, we shall not see the complete pass-through of the MSP increase in inflation.

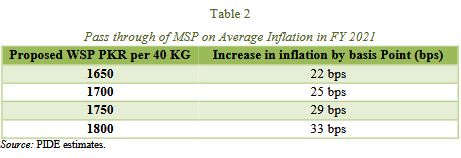

PIDE has developed several scenarios for the impact of wheat minimum support price increase National Inflation in the baseline case. Our findings suggest that if the government sets MSP PKR. 1,750 per 40 kgs., it will increase inflation by 29 bps. However, a bumper crop and good governance may reduce the pass-through on inflation and vice versa. Therefore, the government has to have reasonable control over the administrative side to have a minimal impact on food inflation.

SOLUTIONS/WAY FORWARD

(a) Wheat or any other subsidy goes to only those farmers who own land; however, most of the farmers in Pakistan do not own lands though not eligible for Bardana—brown bags through which the Government of Pakistan buys wheat. Most of the benefits through Wheat MSP goes to middlemen and millers who operate in grey areas.

(b) PIDE has long argued that the wheat market has never been allowed to develop because of the government’s excessive involvement. It is not surprising that this market exhibits a situation of excess supply or demand every few years. This has amply been seen in all countries that have government-maintained markets (for instance, the former Soviet Union and other centrally planned economics). Government wheat procurement does not incentivize small farmers, but on the cost of small farmers, mills are incentivized through MSP (Haider, 2020). The circular debt of wheat procurement is then put to ordinary man’s shoulder regressive taxation. Flour mills are obligated to produce 65% flour from the wheat, but they do not make it and instead make other by-products, which can then be exported or sold locally at better prices. If proper record keeping is done, then millers would be required to produce 65% flour.

(c) The institutional problem in wheat procurement is also a big issue because of widespread corruption and rent-seeking, which increases transaction costs and uncertainty, discourages marketing investment and participation, and ultimately leads to a negative fiscal impact for the Government (Ahmad et al., 2005). So what is the solution? The government should slowly step out of the food market and let the market function freely. The government can divert vast sums of subsidies to developing physical infrastructure and agricultural research for better seed qualities. However, to avoid extreme food price fluctuations, the government needs to monitor wheat production and availability.

(d) The government should withdraw from fixing the minimum support price for wheat, framing wheat export policy, and regulating legislation regarding support price regime. The government’s role should be for encouraging R & D, monitoring quality, and maintaining buffer stocks for fine-tuning in cases of extreme shortages. The international market can readily supply wheat at short notice. With the market in place, the probability of a shortage will be minimal. Like every other county, the government will monitor and remain ready to intervene in extreme circumstances.

(e) The retail wheat price is much higher than the proposed MSP; therefore, we shall not see the complete pass-through of the MSP increase in inflation. If the government sets PKR 1,750 MSP, it will increase inflation by 29 bps. However, a bumper crop and good governance may reduce the pass-through on inflation and vice versa. Therefore, the government has to have reasonable control over the administrative side to have a minimal impact on food inflation.

(f) The government should take appropriate measures to reduce the gap between wheat MSP and retail price. The government should promote competitiveness in the wheat market to reduce market distortion costs and avoid illegal trading. The cost of wheat production is high, with low productivity in Pakistan than India and Iran. The government can tackle inflationary pressures by promoting competitiveness in the wheat market. Anjum and Zia (2020) argue that high yielding and relatively low-risk varieties need to be introduced by involving the private sector. Knowledge-based innovations and interventions will increase competitiveness, ensure future food security, and reduce trade deficit (Anjum, 2020).

REFERENCES

Dorosh, Paul and Salam, Abdul (2008). Wheat markets and price stabilisation in Pakistan: An analysis of policy options. The Pakistan Development Review, 47(1), 71–87.

Ghani, Ejaz (1998). The wheat pricing policies in Pakistan: Some alternative options. The Pakistan Development Review, 37(2), 149–166.

India Today (2018). How is MSP for crops calculated and what are its flaws?. Retrieved 18 October 2020, from https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/msp-for-crops-calculated-and-flaws-1281042-2018-07-09

Khan, M.H and Schimmelpfennig, A. (2006). Inflation in Pakistan: Money or Wheat? (IMF Working Paper WP/06/60).

Shahzad, M. A., Razzaq, A., & Qing, P. (2019). On the wheat price support policy in Pakistan. Journal of Economic Impact, 1(3), 80–86.

ANNEXURE 1

Determinants of Wheat MSP in India

India’s government has a mechanism in place, and the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) recommends MSP for major agricultural commodities in India. Every year, MSPs are announced for 23 crops in India, and the government procures only paddy, wheat, and, to a limited extent, pulses. The cost of production in India is a calculator on three levels:

- (1) A2: includes such as seeds, fertilizer, labour;

- (2) A2+FL, which includes the implied cost of family labour (FL); and

- (3) C2, which includes the implied rent on land and interest on capital assets over and above A2+FL.

The Indian government currently adds 50 percent of the value obtained by adding A2 and FL to fix the MSP of crops, which means 50% of profit goes to the farmers after A2 and FL. Though if the cost of C2 is added, then the profit accounts for around 12-20%. Every season Rabi and Kharif, The Commission uses micro-level data and aggregates at the district, state, and country levels. The information/data used by the Commission, inter-alia include the following (India Today, 2018):

- Cost of cultivation per hectare and structure of costs in various regions of the country and changes therein;

- Cost of production per quintal in various regions of the country and changes therein;

- Prices of various inputs and changes therein;

- Market prices of products and changes therein;

- Prices of commodities sold by the farmers and of those purchased by them and changes therein;

- Supply related information—area, yield and production, imports, exports and domestic availability and stocks with the Government/public agencies or industry;

- Demand related information—total and per capita consumption, trends and capacity of the processing industry;

- Prices in the international market and changes therein, demand and supply situation in the world market;

- Prices of the derivatives of the farm products such as sugar, jaggery, jute goods, edible/non-edible oils, and cotton yarn and changes therein;

- Cost of processing of agricultural products and changes therein;

- Cost of marketing—storage, transportation, processing, marketing services, taxes/fees and margins retained by market functionaries; and

- Macro-economic variables such as general level of prices, consumer price indices, and those reflecting monetary and fiscal factors.

ANNEXURE 2

ANNEXURE 3

Institutional Mechanism of Minimum Support Price (MSP) in India

- India being an agrarian economy, has established the agriculture sector, which contributes to around three-fourths of the GDP and employs more than four-fifths of the population.

- Reforms in the Indian agricultural policy were spearheaded in the mid-1960s in the wake of the food shortages. Resultantly, the policy reforms which were followed focused on achieving food grain self-sufficiency.

- The institutional reforms which were followed to strengthen agricultural production and boost agrarian production included: land reforms, administrative and managerial changes in the sector, credit extension schemes, application of technology, agricultural research, and price support policies such as Minimum Support Price (MSP).

- Prices of agricultural produce are unstable due to informational asymmetries, lack of market coordination, and inconsistency in the supply of crops. The future supply of crops is determined by the ways prices fluctuate in the market. A farmer may decide to withdraw sowing a particular crop in the future because of the sharp fall in the current market price. The result is a sharp fall in the supply of that crop in the following year concomitant with a sharp increase in consumers’ price.

- MSP helps in addressing the issue described above. The government fixes MSP for major agricultural products (such as rice, wheat, maize, bajra, pulses, etc..- 24 items). Through MSP government ensures that farmers will receive a fair amount of price (fixed by the government) for their upcoming crops to invest in agricultural commodities production.

- Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) recommends MSP for major agricultural commodities in India. CACP operates as a statutory body that prepares and submits reports about the pricing of products for Kharif and Rabi seasons and recommends MSP to the State and Central Governments. The State Governments submit reports to the Central Government, which takes the final decision after considering the supply/demand situation of the agricultural produce.

- The successful implementation of MSP is contingent on the benefits it yields to the farmers. To ensure success, the informational lacunae should be minimum. Farmers should know the current MSP, its announcement, procurement procedure, government facilitation, and mechanisms for providing on-time payments. Secondly, it is also vital to compute and record the cost of cultivation and compare it with the MSP. This will yield if the farmer is in surplus or not. Thirdly, to ensure that farmers do not opt for distress selling, the operational procurement mechanism should be institutionalized with minimum structural inadequacies, administrative issues, and informational asymmetries.

- Most recently (September 2020), India’s government has decided to increase the MSP of wheat to INR. 1975 (PKR. 4,345) per quintal or PKR. 1,738 per 40 kgs. The official data reveals that expected returns to farmers over their costs are the highest in wheat (106%). The official data shows that the number of farmers who sow wheat and benefited from the MSP has doubled (112 percent increase) since 2016-17 in India.

ANNEXURE 4

Institutional Mechanism of Minimum Support Price (MSP) in Pakistan

- In Pakistan, federally, wheat is procured through Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation (PASSCO) and provincially through Punjab Food Department. Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) decides the wheat price support policy of Pakistan. ECC is a Federal institution in service of the PM of Pakistan, also the committee’s chairperson. The committee proposes policies to the PM on political and economic issues.

o The committee also defines several objectives on the wheat price support policy of Pakistan. The objectives are outlined along the axis of increasing wheat productivity, supporting farmers’ incomes and providing food security through subsidies and price controls. These objectives are supported by literature that asserts that support prices protect farmers and traders and increase crop yields.

- The interventionist policy approach adopted by the Government of Pakistan focuses on input and output price regulations, aiming to stimulate consumers and producers through subsidies and tax plans.

- For protecting farmers from market price fluctuations and ensuring that consumers are provided with a stable supply of agricultural commodities, the Punjab government and the federal governments have set support prices and devised channels to ascertain the procurement of wheat. Over the years, interventionist policies have helped farmers and consumers from monopolies.

Despite favourable results, wheat procurement, and support prices have resulted in financial burdens on the Punjab government. Wheat is purchased at a price above the international price, and the inability to sell the final product in the global market has nosedived the Pakistan economy.

- The decision to increase wheat minimum support price from PKR. 1,400 to PKR. 1,745 per 40 kg is tricky as it may cause the country to lose its competitiveness in the international market.

o In comparison to India, the cost incurred on wheat production is much high in Pakistan. To ensure farmers’ profits, the government raises the MSP due to higher production costs.

o Subsidizing wheat procurement and release guarantees higher MSP. This policy action has been practiced by the Government of Pakistan, which has put financial burdens on government finances.

o The consumers, on the other hand, are also adversely impacted by the higher wheat prices. To reduce production costs, input subsidies can be facilitated to the farmers rather than subsides on purchase prices. The reduction in input costs will reduce output prices, which may raise farmers’ profits and consumer surplus.