Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

What’s your Degree Worth? Return to Education, Employability, and Upskilling Workforce in Pakistan

With an overabundance of unemployed/underemployed university graduates and a scarcity of qualified skilled workers, Pakistan’s education and labor markets are structurally unbalanced. The focus on expanding educational access has fallen short of ensuring the labor force’s competitiveness in the country. Workforce skilling or upskilling with smart integration into global value chains and local market needs has received structurally insufficient attention. The shortage of skilled workforce is discussed repeatedly (ILO, 2022; Tribune, 2021). The nexus between the returns to conventional and skilled education, employability, and barriers to up/skilling the workforce is imperative to understand, as it may provide a holistic insight into gaps that are curial to address.

Skills and Labour Market

The labor market’s skill requirements are changing due to technological advancement. It is unclear whether current education systems (both mainstream and technical) are providing graduates with the necessary skills to meet the needs of the labor market. Nomura (2019) discusses that advanced and emerging economies are experiencing an increased demand for non-routine cognitive and socio-behavioral skills. The value of combinations of several skill types appears to rise, while the demand for routine job-specific skills is decreasing. A holistic approach to skill development, including but not limited to socio-behavioral, cognitive, and technical skills, is needed right from early childhood development and education (Nomura, 2019).

In Pakistan, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is used as the synonym for skill training. The TVET education curriculum notably lacks training in cognitive and behavioral skills, which are essential for modern job market skills. Even with the technical training side, there are serval issues with the current TVET education system, including catching up-with market skills demands, courses diversification, outreach, and accessibility, to name a few. Less than one percent of students opt for TVET education in Pakistan. The structural targeting at the policy level to encourage students from rural areas, school dropouts, or who scored low grades to pursue TEVT also contributed majorly to the social belief that TVET is far less socially prestigious than mainstream education. Similarly, (Khan, 2021) argues that the TVET system in Pakistan is underfunded and less developed, which reflects the poor quality of TVET services. Consequently, students and parents are not drawn to the TVET system.

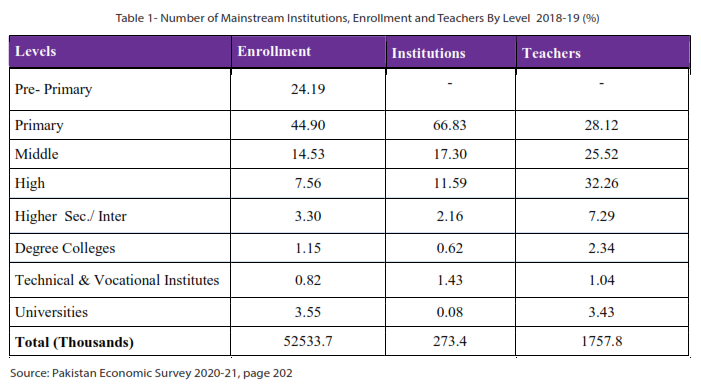

The composition of enrollment, number of institutions, and teachers across education levels show that Pakistan still struggles to improve the educational profile of the population (see Table 1). About 69% of the enrollment is in elementary education (pre-primary and primary), which is desirable considering the young age population in the country; however, the percentage of the population who drop out after elementary education or quit education altogether is considerably high. It is also important to note that at the national level, 32 % of children aged 5-16 are currently out of school (Pakistan Economic Survey 2020-21). About 84% of the students in the formal education system study in primary and middle education grades. Degree colleges and universities together account for 4.69% of students’ enrollment. Notably, there are 3900 public and private TVET institutes, but only 0.82 % of the students opt for vocational and technical training.

Societal Perception towards Technical Education in Pakistan

One of the reasons students in South Asian nations do not favor pursuing technical and vocational education is that society values getting a general academic degree as more prestigious than manual labor and training (Vollmann, 2010). Many students in Pakistan prefer not to pursue vocational education due to social expectations, which adds to a skills deficit in technical fields. The idea that TEVT has been created for a particular group or socio-economic class of individuals indicates society’s orientation towards TEVT (Maskey, 2019). Studies show that parents from lower socio-economic backgrounds encourage their kids to enroll in technical and vocational courses (Ayub, 2015; Ohiwerei & Nosu, 2009). Maskey (2019) argues that effective implementation of technical programs is only achievable until society’s perception of the gap between general education and technical and vocational education is eliminated. Many young people are reluctant to enroll in technical education or vocational training because they fear losing their “status as an educated person” or peer and family pressure (Maskey, 2019).

Employability and Education

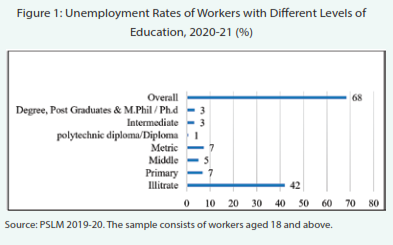

The overall unemployment rate among the population with formal education is concerning compared to the population without formal education (Figure 1). Across different education levels, the lowest unemployment rates are among the population with a polytechnic diploma. Recent studies from Pakistan also show the same concern. For instant, Haque & Nayab (2022) looked at the youth (15-29) un/employment trends and emphasized on talent-focused opportunity approach to address the issue. On the employer side, Humayun (2022) identified recent graduates lacking employability skills in Pakistan. Employers have expressed concern about Pakistani graduates’ lack of core skills and personal attributes. The study shows that core skills, i.e., creativity, critical thinking, interpersonal, and leadership skills, are highly relevant in the labor market. Humayun (2022) proposed that institutions that provide higher education should regularly assess the demands of the industry and educate graduates accordingly.

What is employability?

Employability is the set of skills, knowledge, attitudes, and personal attributes that may help individuals succeed in a chosen professional field, or as an entrepreneur, or in self-employability (IGI-Global, 2022). Employability is a lifelong process that needs structural attention to help the population develop skills, behaviors, and attitudes that will enable them to succeed in the workplace and other areas of their lives.

Return to Education

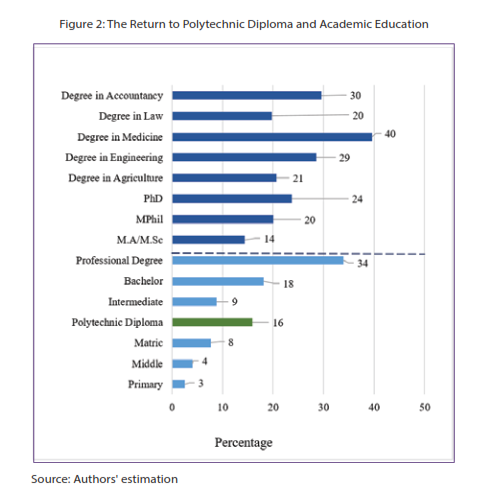

We have calculated returns to education for different education levels. The results show that higher earnings are associated with higher education and professional degrees. However, returns to education for a population with university degrees, i.e., Undergrad, Master, and MPhil, are considerably low. The returns to education with a Ph.D. degree are highest; however, Ph.D. holders account for a minor portion of overall university graduates. A more significant proportion of university graduates are Bachelor, Master, or MPhil degree holders. It is noteworthy that returns education for a population with a technical diploma is higher than that of a population with high school (Inter) or metric or below education (see Figure 2[1]). Despite the high returns for technical diplomas, the high enrollment in inter or degree levels, as compared to enrollment in technical education, explains the low demand for technical education.

__________________________

[1] First we estimate the above equation without splitting the Profession into its sub categories. After that to see which profession offers more return we estimate the above equation with different types of professions. The rate of returns from RWM_NEVER_ATD_SCH, PRIMARY, MIDDLE, MATRIC, DIPLOMA, INTER and BACHELOR are approximately the same. Therefore, in Figure 2 we combined both results but used different colors (light blue for combined profession and dark blue for different types of professions) and also split it with dotted line. Also note that all coefficients are significant at a 1% level of significance. The returns to workers who possess literacy and numeracy skills but never attended school is 0.83%.

Mincerian Earning Function

Our empirical strategy to estimate an earnings function is based on the human capital model introduced by Becker (1964) and Mincer (1974). Accordingly, the logarithm of monthly earning ( is the linear function of schooling (, labor market experience ( imputed from age less years of education less six, and other socio-economic characteristics such as (marital status, region, type of school, gender, nature of work. It is expressed as

Different years of education have a different effects on the earnings of individuals. For this purpose, an eight-level spline of school years based on the education system of Pakistan has been used, i.e., workers who possess literacy and numeracy skills but never attended schools, Primary, Middle, Matric, Polytechnic Diploma, Intermediate, Bachelor and Professionals.

Data: The present study uses the data of the PSLM for the year 2019-20. The sample is consisting 187395 wage earners having positive earnings and an age of 18 and above. Illiterate earners are considered as references category (base category) and level of schooling is dichotomous variable.

Estimation Technique : Mincerian Earning Function is estimated using White heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors and covariance in the ordinary least square (OLS) method to tackle the heteroscedasticity problem in cross-sectional data.

Returns to Education- Data and Estimation

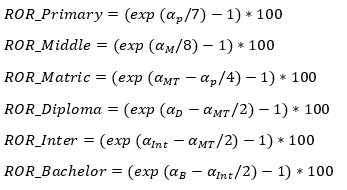

The present study uses the data of the PSLM for the year 2019-20. The sample is consisting 187395 wage earners having positive earnings and an age of 18 and above. Return to education is calculated based on Mincer Wage Earning Equation. By assuming that the increase in earnings between educational levels is exponential, the definition of the Mincerian return transforms the dummy variable to an annually equivalent increment in earnings (Kahyarara & Teal, 2008). The rates of return are defined as follows

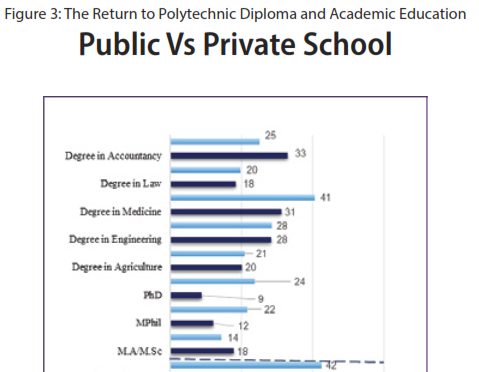

Due to the type of school-based structural differences in earnings, separate models are estimated for workers with public and private school types. The returns to education consistently increase with the education level for those who have received education from private institutions. The results show that returns to education for elementary, secondary, and University education (i.e., bachelor’s and master’s) are higher for the population who have received education from a private institute as compared to the population with the same education levels who studied in public institutions. However, returns to the education for the population with a polytechnic diploma from public institutions has higher returns than those who earned a diploma from a private institute (see Figure 3). Returns to education for MPhil, Ph.D., Medicine, and Law degree holders who have received education from a public institute are higher than their counterparts who have received education from private institutes.

Due to the type of school-based structural differences in earnings, separate models are estimated for workers with public and private school types. The returns to education consistently increase with the education level for those who have received education from private institutions. The results show that returns to education for elementary, secondary, and University education (i.e., bachelor’s and master’s) are higher for the population who have received education from a private institute as compared to the population with the same education levels who studied in public institutions. However, returns to the education for the population with a polytechnic diploma from public institutions has higher returns than those who earned a diploma from a private institute (see Figure 3). Returns to education for MPhil, Ph.D., Medicine, and Law degree holders who have received education from a public institute are higher than their counterparts who have received education from private institutes.

Discussion

The up/skilling workforce is essential for economic growth. To better match the skills required and those available, educational systems should be receptive to the needs of a productivity-driven economy. This may be achieved through offering demand-specific technical training and lifelong learning of basic cognitive, social and behavioral skills. Mere expansion of education may not produce a knowledgeable, creative, and skilled workforce that is key to surviving in fast-paced economies. A concerning situation is a high rate of un/underemployed university graduates while employers are dissatisfied over not finding graduates with the required skills.

The returns to education for graduates with Bachelor, Master, and MPhil degrees are considerably low. The situation concerns the number of resources required to complete these degrees (regardless of discipline), which should yield higher returns. The situation leads to questions: What are the reasons behind considerably low returns to education for Bachelor/Master/ MPhil graduates? How are graduates with Bachelor/Master/ MPhil degrees skilled? What are the skill gaps? Why are returns to education higher for those who received education from private institutions?

Moreover, the percentage of the population pursuing formal skill education is depressingly low. In a country of 220 million people, the proportion of students who are currently enrolled in TVET education does not even account for 1 % of the total enrollment at all education levels. This is not to say that people are not skilled or working in professions that require skills; probably, the school dropout or population who do not have any formal education might be working in professions that require technical skills. But not having formal education would lead to several problems, including but not limited to stagnant skill acquisition, low chances of upward social mobility, slim chances to enter a formal job market that needs certification, and risk of facing labor rights violations, to name a few.

Despite having better employability chances and returns to education, technical education in Pakistan is not the first choice for many students. This is partly because technical education needs structural improvements, but societal perceptions about technical education are mainly negative. Effective technical education implementation is only achievable when the gap between societal prestige associated with mainstream education and technical and vocational education is minimized. Merging technical and mainstream education systems in urban and rural areas would help in the acceptance of technical education in society. Skilled education can also be incentivized with job placement support. Moreover, age, gender, and geographically disaggregated data can provide insight into the intersectionality of the issue and help target the specific needs accordingly. Systematic methods are needed to monitor labor market demand at both federal and provincial levels.

References

Ayub, H. (2015). Factors affecting student’s attitude towards technical education and vocational training. In ICBEM (International Conference on Business, Economics and Management) in Pattaya, Thailand, on (pp. 15-16).

Ayub, H. (2017). Parental influence and attitude of students towards technical education and vocational training. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 7(7), 534-538. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2017.7.7.925

Haque, N. U. & Nayab, Durr-e (2022). Pakistan Opportunity To Excel: Now And The Future (No. 2022: 1). Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

Humayun, S. (2022). Higher Education and Employability in Pakistan: Perspective from Employer and Business Graduates. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

IGI Global (2022). https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/employability/9751

ILO (2022). Skills and employability in Pakistan. https://www.ilo.org/islamabad/areasofwork/skills-and-employability/lang–en/index.htm

Kahyarara, G., & Teal, F. (2008). The returns to vocational training and academic education: Evidence from Tanzania. World Development, 36(11), 2223-2242.

Khan, J. (2021). Employment and Skills. http://staging.letsworkitvip.com/wp-content/uploads/pip-0380-employment-and-skills.pdf

Maskey, S. (2019). Choosing technical education and vocational training: A narrative inquiry. Journal of Education and Research, 9(2), 9-26.

Maskey, S. (2019). Choosing technical education and vocational training: A narrative inquiry. Journal of Education and Research, 9(2), 9-26.

Nomura, S. (2019). Pakistan – Skills Assessment for Economic Growth, World Bank Group. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1286756/pakistan/1885297/ on 12 Sep 2022. CID: 20.500.12592/tbhb3z.

Ohiwerei, F., & Nwosu. B. (2009). Vocational Choices among Secondary School Students: Issues and Strategies in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Business Management 1(1): 1-5, 2009, 5.

Puerta, M. S., & Rizvi, A. (2018). Measuring Skills Demanded by Employers: Skills Toward Employment and Productivity (STEP). World Bank, Washington, DC.

Tribune (2021, Nov 28). ‘Lack of skilled workforce hindering exports.’ https://tribune.com.pk/story/2331418/lack-of-skilled-workforce-hindering-exports

Vollmann, W. (2010). The challenge of technical and vocational training and education in rural areas: The case of South-Asia. Journal of Education and Research, 2, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.3126/jer.v2i0.7623