Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Threats Across the Borders: Tackling Transboundary Environmental Injustice

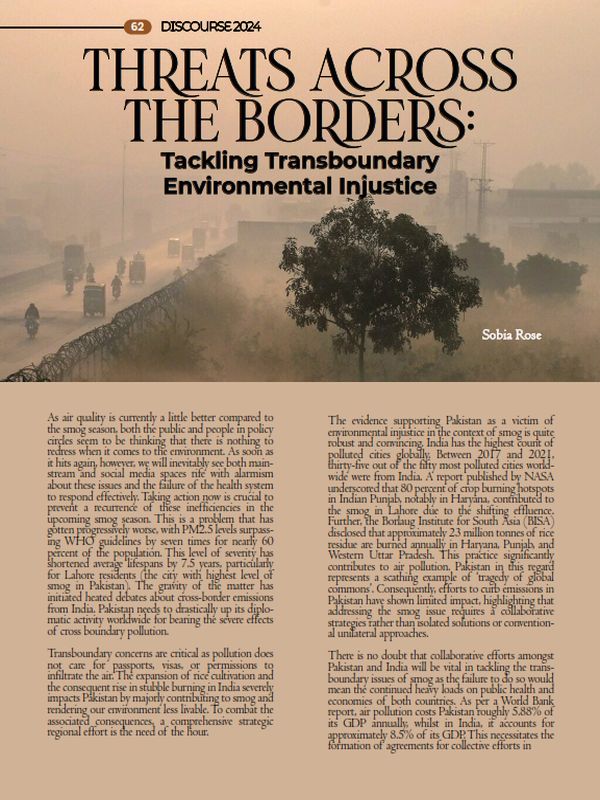

As air quality is currently a little better compared to the smog season, both the public and people in policy circles seem to be thinking that there is nothing to redress when it comes to the environment. As soon as it hits again, however, we will inevitably see both mainstream and social media spaces rife with alarmism about these issues and the failure of the health system to respond effectively. Taking action now is crucial to prevent a recurrence of these inefficiencies in the upcoming smog season. This is a problem that has gotten progressively worse, with PM2.5 levels surpassing WHO guidelines by seven times for nearly 60 percent of the population. This level of severity has shortened average lifespans by 7.5 years, particularly for Lahore residents (the city with highest level of smog in Pakistan). The gravity of the matter has initiated heated debates about cross-border emissions from India. Pakistan needs to drastically up its diplomatic activity worldwide for bearing the severe effects of cross boundary pollution.

Transboundary concerns are critical as pollution does not care for passports, visas, or permissions to infiltrate the air. The expansion of rice cultivation and the consequent rise in stubble burning in India severely impacts Pakistan by majorly contributing to smog and rendering our environment less livable. To combat the associated consequences, a comprehensive strategic regional effort is the need of the hour.

The evidence supporting Pakistan as a victim of environmental injustice in the context of smog is quite robust and convincing. India has the highest count of polluted cities globally. Between 2017 and 2021, thirty-five out of the fifty most polluted cities worldwide were from India. A report published by NASA underscored that 80 percent of crop burning hotspots in Indian Punjab, notably in Haryana, contributed to the smog in Lahore due to the shifting effluence. Further, the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) disclosed that approximately 23 million tonnes of rice residue are burned annually in Haryana, Punjab, and Western Uttar Pradesh. This practice significantly contributes to air pollution. Pakistan in this regard represents a scathing example of ‘tragedy of global commons’. Consequently, efforts to curb emissions in Pakistan have shown limited impact, highlighting that addressing the smog issue requires a collaborative strategies rather than isolated solutions or conventional unilateral approaches.

There is no doubt that collaborative efforts amongst Pakistan and India will be vital in tackling the transboundary issues of smog as the failure to do so would mean the continued heavy loads on public health and economies of both countries. As per a World Bank report, air pollution costs Pakistan roughly 5.88% of its GDP annually, whilst in India, it accounts for approximately 8.5% of its GDP. This necessitates the formation of agreements for collective efforts in implementing a shared system of tracking air quality across borders which aid in understanding the sources of smog and their relative impacts, as well as harmonising the environmental regulations for emission standards and practices. The investment in shared advanced pollution control technology and public engagement in emission reduction initiatives is also imperative.

International environmental norms, established notably during the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, emphasise the principle of common responsibility with differentiated roles. This means all states share the duty to protect the environment and curb carbon emissions, with those who contribute more shouldering a greater responsibility. International Law also prohibits activities causing harm to other countries, thus offering a basis for a strong case to curb transboundary air pollution in the subcontinent. More broadly, the Trial Smelter Case (USA versus Canada) underlines that a state cannot permit activities on its land that jeopardise life or property in another state according to International Environmental Law. Instances like the Singapore-Malaysia haze issue, where Indonesia’s burning of palm trees affected neighboring countries, illustrates the importance of collective action all around the world: at least when it comes to environment related issues.

To tackle the issue of air pollution in South Asia, a joint regional framework is an urgent requirement. If pursued and applied with full might (political will), this will certainly reduce the emission in affected countries. Pakistan has already emphasised the necessity for bilateral discussions on air pollution and smog during COP-26 in 2021 and it still wants the issue to be resolved for the sake of our future generations. Pakistan also proposed hosting a regional conference focused on transboundary air pollution and smog in accordance with The Malé Declaration, 1998. However, when considering Indo-Pak relations, the stipulations demand a thorough examination of practical opportunities to help materialise a collaborative framework.

Let us assess the effectiveness and drawbacks of the The Malé Declaration. This declaration emphasised the necessity for regional collaboration in managing transboundary air pollution. However, the countries’ thirst for economic growth has obstructed its implementation. Consequently, its goals remained unfulfilled. The recurring smog incidents in South Asia vividly illustrate the limitations of this agreement, and the current air quality crisis demands an urgent need to overhaul this framework, potentially under the guidance and support of organisations like ICIMOD and SAARC. The shared limitations among South Asian nations, especially the lack of monitoring facilities and resources, continue to persist. Unlike China, which has the capacity to independently address its issues without extensive cooperation with neighbours, South Asian countries face a myriad challenges. Therefore, the revitalisation of this declaration considering new requirements should serve as a bridge, aiming to alleviate any geopolitical tensions and foster cooperation.

The severity of the smog issue could serve as an opportunity for India and Pakistan to break the historic deadlock and collaborate on mutual environmental challenges. But the reality is bitter. Politics often strays from justice, swayed by power dynamics. The current right-wing leadership’s orientation makes it seem like cooperation, fairness and justice are a pipedream. Further, economic disparities between Pakistan and India further diminish prospects for collaboration. The sabotage of the Indus Water Treaty and recent violations of International Law regarding Kashmir restrict options of seeing regional cooperation on future prospects. However, assistance from international environmental organisations and regional economic powers can make it possible.

The author is a Research Fellow at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad.