Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

The Significance of Oral Histories in Pakistan

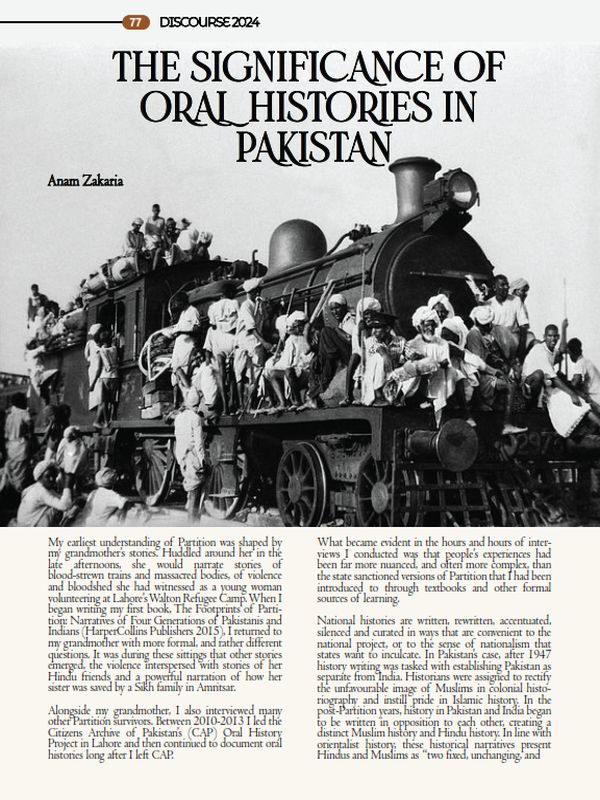

My earliest understanding of Partition was shaped by my grandmother’s stories. Huddled around her in the late afternoons, she would narrate stories of blood-strewn trains and massacred bodies, of violence and bloodshed she had witnessed as a young woman volunteering at Lahore’s Walton Refugee Camp. When I began writing my first book, The Footprints of Partition: Narratives of Four Generations of Pakistanis and Indians (HarperCollins Publishers 2015), I returned to my grandmother with more formal, and rather different questions. It was during these sittings that other stories emerged, the violence interspersed with stories of her Hindu friends and a powerful narration of how her sister was saved by a Sikh family in Amritsar.

Alongside my grandmother, I also interviewed many other Partition survivors. Between 2010-2013 I led the Citizens Archive of Pakistan’s (CAP) Oral History Project in Lahore and then continued to document oral histories long after I left CAP. What became evident in the hours and hours of interviews I conducted was that people’s experiences had been far more nuanced, and often more complex, than the state sanctioned versions of Partition that I had been introduced to through textbooks and other formal sources of learning.

National histories are written, rewritten, accentuated, silenced and curated in ways that are convenient to the national project, or to the sense of nationalism that states want to inculcate. In Pakistan’s case, after 1947 history writing was tasked with establishing Pakistan as separate from India. Historians were assigned to rectify the unfavourable image of Muslims in colonial historiography and instill pride in Islamic history. In the post-Partition years, history in Pakistan and India began to be written in opposition to each other, creating a distinct Muslim history and Hindu history. In line with orientalist history, these historical narratives present Hindus and Muslims as “two fixed, unchanging, and essentially mutually antagonistic communities [reinforcing] a communal rendering of the past.”[1] In the post-Partition years this has also meant that depending on what side of the border one is on, the national memory of Partition is remembered and evoked differently.

In Pakistan, Partition violence is selectively framed as Hindu and Sikh violence on Muslims whilst in India Muslims are painted as treacherous and disloyal to the state; Muslims serve as villains in the Indian national imaginary. In Pakistan, Partition is tied to nation-making and the violence is couched as an essential sacrifice and martyrdom paid by Muslims for freedom from not only the British Raj but also Hindu subjugation.[2] In India, Partition has historically been framed as a breakup of the motherland at the hands of treacherous Muslims, and as an illegitimate demand of the Muslim League.[3] But beyond these national imaginaries lie people’s lived experiences. Whilst state histories appropriate or weaponise selective aspects of people’s experiences, and many times also shape people’s memory, people’s lived reality is messy and cannot be neatly packaged into linear and black and white versions of history. This reality unearths itself through oral history work.

In the oral history interviews I have conducted on the 1947 Partition, survivors have at times narrated being attacked and rescued by members of the ‘other’ community during the same interview setting. Indian political psychologist Ashis Nandy’s research on Partition, which entailed 1500 interviews, also indicated that 40 per cent of his interviewees recalled stories of being helped through the “orgy of blood and death by someone from the other side.”[4] That these violent memories coexist with softer recollections are the truth for many Partition survivors, blurring the neat lines between perpetrator and victim carved out by states.

In my more recent work on 1971, the power of oral histories is even more evident. In the Pakistani state history, 1971 and the birth of Bangladesh has either been omitted, trivialised or fabricated. 50 years after the war, Pakistan continues to deny the genocide of Bengali people and other ethnic minorities. When the violence of 1971 is remembered, the state selectively remembers bloodshed against the Urdu speaking community and erstwhile West Pakistanis settled in then East Pakistan. The genocidal violence unleashed, backed by the state machinery, is ignored, denied or framed as an Indian conspiracy. Any violence by the Pakistan Army that is mentioned is legitimated as a justified response in the name of national integrity or as ‘collateral damage’.

Against this selective silencing and forced amnesia, oral histories offer one of the only sources of memory, and in their remembrance, as a form of resistance to state erasure. Whilst many Pakistanis settled in West Pakistan relied on the state machinery for news, and during my interviews with them reinforced state narratives, interviews with people based in East Pakistan as well as intellectuals and activists unfolded another telling of events. These oral histories shed light on the social, economic and political discrimination against East Pakistanis after Pakistan’s creation and the scale of violence inflicted upon Bengali bodies and ethnic minorities by the state in 1971. It was through these oral histories that, I, for the first time, found out about a resistance movement in Pakistan during the war. Though small in scale, it included people like the late I.A Rahman, Ahmad Salim, Tahira Mazhar Ali and many others who criticised state action. In the recalling of these memories, they continued to challenge state silencing in the years after the war.

In a context where conventional sources of learning – from textbooks to museums – often narrate distorted, censored, morphed or selective histories, people’s personal experiences of these larger meta events can offer us a far more nuanced understanding of the past. Oral histories serve as resistance, as a political act of remembrance against forced forgetting, challenging state amnesia and offering a different way of learning about the past and its implications on the present.

The author is the author of three books, most recently 1971: A People’s History from Pakistan, Bangladesh and India (Folio Books 2023).

[1] Ali Usman Qasmi, “A Master Narrative for the History of Pakistan: Tracing the Origins of an Ideological Agenda” in Modern South Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press 53(4): 1066-1105 (2019)

[2] Ayesha Jalal, “Conjuring Pakistan: History as Official Imagining” in International Journal of Middle East Studies 27(1): 73-78

[3] Krishna Kumar, Peace with the Past, https://www.india-seminar.com/2003/522/522%20krishna%20kumar.htm

[4] Ashis Nandy, Pakistan’s latent ‘potentialities’, Radio Open Source