Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

The Assumed Shortage of Housing in Pakistan (PIDE Policy Viewpoint 36:2022)

The Assumed Shortage of Housing in Pakistan

Prepared by: Durr-e-Nayab

“We are short of 10 million housing units” has been the clarion cry in politics, media and the donor-driven research for the last 10 years.

Given an average household size of well over six persons[1], this means that nearly one-third of the population is without housing. Do we see such a huge number of people living on footpaths, side of roads, under bridges or in any open area? Thankfully, NO!

We cannot find any clarity on where this huge figure of 10 million housing shortage came from!

- Media (print, electronic and social) uses it referring to it as a World Bank estimate, while various World Bank[2],[3] publications quote a report submitted to the State Bank as the source, along with a study done by the International Growth Centre (IGC)[4] (a DFID funded global research effort out of the LSE and Oxford).

- The IGC report cites a SBP[5] report, but interestingly, the said report gives a lower per annum figure than the one quoted by the IGC.

- A more recent State Bank document[6] gives no source and just gives the number as a given.

- Some WB documents refer to a House Building Finance Company Limited’s presentation[7] as the source but nowhere does one find the exact method used to reach the oft-repeated number.

The worst part is that the government also uses this estimate without ever questioning its validity. And sadly we have based policy on this assumption and initiated a large public housing effort at considerable cost.

A few indicators to judge the housing conditions include congestion or crowding, security of tenure, provision of civic amenities, structural quality and cultural adequacy.[8] The Pakistan Social and Living Measurement (PSLM) survey, conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), provides us with the opportunity to look into most of these factors, and we do so using its 2019-2020 round. Since urban and rural Pakistan exhibit quite different trends we look at them separately, along with some provincial patterns.

IS CONGESTION THE SOURCE OF “HOUSING SHORTAGE”?

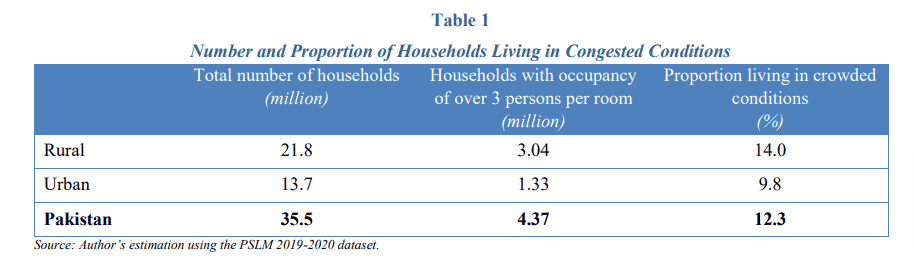

Using the definition given by the UN-Habitat[9], “a house is considered to have a sufficient living area for the household members if not more than 3 people share the habitable room that is a minimum of 4m2 in area”. The 4m2 was rightly upgraded to 9m2, as the measurement was too small.

We do not get room sizes in the PSLM, but the number of living rooms is covered in the survey. Since 9 sq2 is a typical size even in informal settlements so we would go by the number of persons per room to estimate congestion.

Our estimates suggest that 4.37 million households, equaling 12.3% of the total households, live in congested conditions, with over two-thirds of these in rural areas (3.04 million), as shown in Table 1. Young children generally live/sleep in their parents’ room so we do not include children aged under 5 years, and half-count those under 12 years, while estimating occupancy per room.

So, if congestion is the rationale behind the 10 million housing deficit, our estimates give a much lower number.

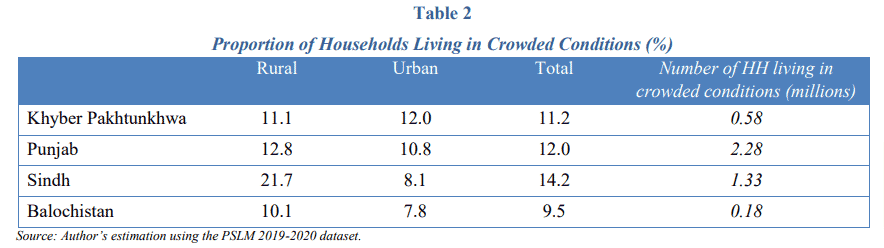

Some inter-provincial differences are also found (see Table 2).

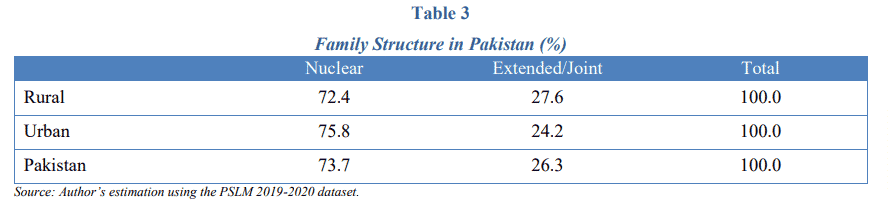

Unlike many countries, joint/extended families are still prevalent in Pakistan, with strong cultural values attached to it. The rates, however, are not as high as one would think as 74% of the households have nuclear set-ups, with not very divergent trends exhibited by rural and urban Pakistan (see Table 3).

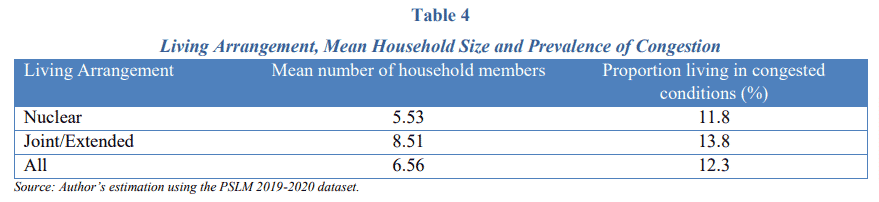

Is the extended/joint family structure the reason behind this congestion? Table 4 shows that joint/extended households do have a larger size (i.e. average household members) and a slightly higher rate for congestion, but the living arrangement is not exactly a huge factor in determining congestion.

IS THE OCCUPANCY STATUS LEADING TO THE NOTION OF ‘DEFICIT’?

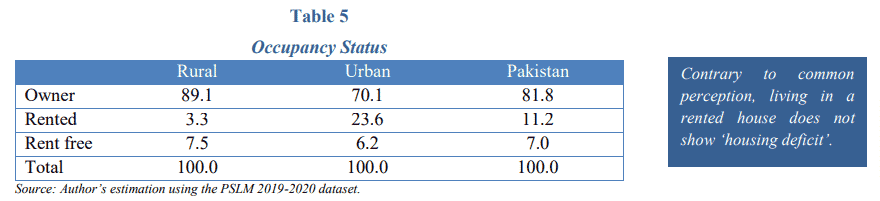

Security of tenure, gauged by the occupancy status in the PSLM, show that this cannot be the case either as Pakistanis predominantly live in owned houses. As Table 5 shows, only a small proportion (11%) lives in rented houses. The sensational deficit estimate makes no mention of the fact that the ownership of dwellings is as much as 82% in Pakistan and rented space is only 11%. In any case, living in rented houses does not represent a ‘deficit’.

ARE THE HOUSES STRUCTURALLY STABLE AND HAVE ACCESS TO AMENITIES?

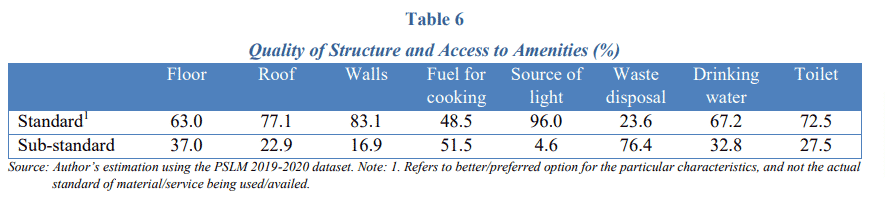

This is where the concern should be. The quality of structure and access to civic amenities need to improve. Table 6 shows that access to basic civic services, like waste disposal, clean drinking water, safe fuel for cooking and a much-improved sewerage system are the issues that need attention to alleviate the quality of housing. Even the very high access to electricity (for light source) does not mean an uninterrupted supply.

SO, WHAT ABOUT THE DEFICIT?

There is certainly not a “deficit of 10 million housing units” in Pakistan. There may be “inadequate housing” in the country, but not “housing shortage’. The deficit is in the quality of life in the houses, not the absence of housing units.

Even if we take into account the high fertility rate and rising population in the country, an additional demand of 0.7 million households every year, as suggested by the IGC study (2016)[10], is very high. Going by the mean household size, it means an additional 4.5 million people needing accommodation- an estimate that appears far from reality. The mean age of the head of the household in Pakistan is 44 years[11]. Given the cultural milieu, young adults do not generally live on their own, thus, suppressing the demand for additional housing that could have been there because of the youth bulge.

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of housing shortage, and the belief that it creates employment, have led the government to push for and subsidise the construction sector. Along with fiscal pressure, it has created an unnatural demand in the real estate market. And while the ‘shortage’ is more in the rural areas, all the housing initiatives are taking place in the urban areas. A forthcoming PIDE study on sectoral productivity over the last decade also shows the construction industry to be among the least productive ones. Any protected/subsidised industry remains unproductive, and the construction industry proves to be no exception.

Migration from rural areas is given as another reason for increased housing demand in urban areas. It is a movement that we at PIDE support, instead of considering it as a problem, we believe that it is through cities that growth happens.[12] Better urban planning, supporting large-scale, mixed-use housing, can go a long way in providing quality affordable accommodation to people. Doing so would deal with whatever housing shortage is there, and more importantly, tackle the quality issue.

PIDE has also shown that the housing shortage arises from the harsh zoning laws and building regulations that favour cars and single-family homes[13]. In addition, PIDE has shown that the shortage of opportunities and high rates on sub-optimal employment[14] reduce the purchasing power of people.

PIDE thesis is that the shortage is that of opportunities not housing. However, sensational figures and perhaps the push for loans has led to a distortion in policy of putting housing before opportunity. Furthermore, opportunity too has been constrained by the same factor as housing which is excessive regulations (see PIDE Sludge Series[15]). Clearly deregulation which is the need of the time has been delayed because policy is driven more by sensational figures than good analysis.

Finally, government should take seriously the PIDE recommendation that local universities and think tanks must be involved in policy, policy research and policymaking. Nothing without being thoroughly reviewed should be taken to the policy table. Our experience tells us that reliance on consultants without domestic oversight has too often proved costly. And the 10 million housing shortage estimate is nothing but yet another proof of this cost!

[1] Average household size comes to 6.56 persons using the PSLM 2019-20.

[2] Enclude, “Final Report: Diagnostic Survey of Housing Finance in Pakistan”. Submitted to the State Bank of Pakistan. November 2015.

[3] World Bank, Project appraisal document on a proposed credit, in the amount of US$145 million to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan for a housing finance project, March 8, 2018.

[4] International Growth Centre (IGC). “Housing inequality in Pakistan: The case of affordable housing.” February 2016.

[5] State Bank of Pakistan, “Quarterly Housing Finance Review”, March 2014

[6] State Bank of Pakistan, “Infrastructure, Housing and SME Finance Department”, March 2019.

[7] House Building Finance Company Limited. “Affordable Housing for Low Income Group.” Presentation. November 11, 2016.

[8] UN Habitat, Metadata on SDGs Indicator 11.1.1, March 2018.

[9] Op cit.

[10] Op cit.

[11] Estimated from the PSLM 2019-2020.

[12] Haque and Nayab, “Cities: Engine of Growth”, PIDE, Islamabad, 2007.

[13] “The PIDE Reform Agenda for Accelerated and Sustained Growth”, PIDE, Islamabad, 2020.

[14] Haque and Nayab, “Opportunities to Excel: Now and the Future”, PIDE, Islamabad, 2020.

[15] PIDE Sludge Series- various issues estimating the cost of bureaucracy, PIDE, Islamabad, 2020, 2021.

PIDE Policy Viewpoint is an initiative for an informed policy-making through evidence-based research conducted at PIDE. It aims to bridge the research-policy gap and improve the public policy process in Pakistan.

Prepared by:

Durr-e-Nayab

Email: [email protected]

Tel: 051-9248094