Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Socialism for the Rich and Capitalism for the poor

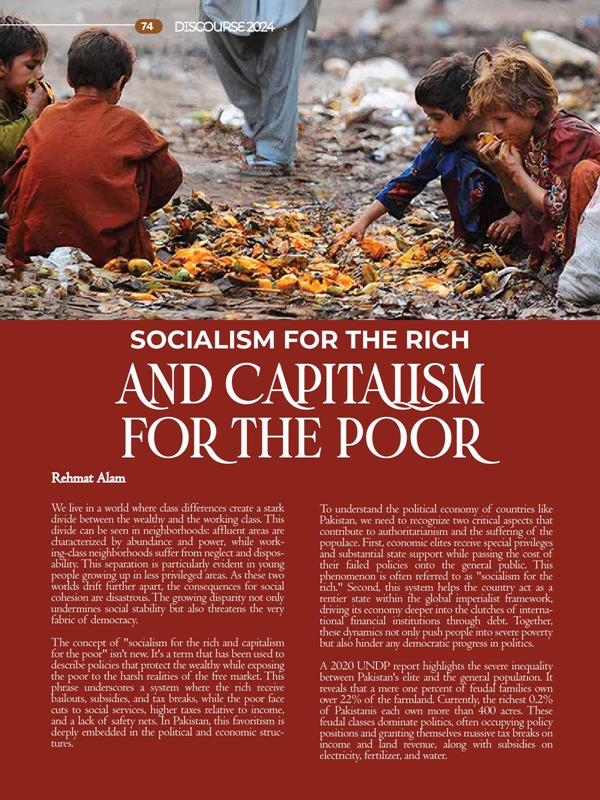

We live in a world where class differences create a stark divide between the wealthy and the working class. This divide can be seen in neighborhoods: affluent areas are characterized by abundance and power, while working-class neighborhoods suffer from neglect and disposability. This separation is particularly evident in young people growing up in less privileged areas. As these two worlds drift further apart, the consequences for social cohesion are disastrous. The growing disparity not only undermines social stability but also threatens the very fabric of democracy.

The concept of “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor” isn’t new. It’s a term that has been used to describe policies that protect the wealthy while exposing the poor to the harsh realities of the free market. This phrase underscores a system where the rich receive bailouts, subsidies, and tax breaks, while the poor face cuts to social services, higher taxes relative to income, and a lack of safety nets. In Pakistan, this favoritism is deeply embedded in the political and economic structures.

To understand the political economy of countries like Pakistan, we need to recognize two critical aspects that contribute to authoritarianism and the suffering of the populace. First, economic elites receive special privileges and substantial state support while passing the cost of their failed policies onto the general public. This phenomenon is often referred to as “socialism for the rich.” Second, this system helps the country act as a rentier state within the global imperialist framework, driving its economy deeper into the clutches of international financial institutions through debt. Together, these dynamics not only push people into severe poverty but also hinder any democratic progress in politics.

A 2020 UNDP report highlights the severe inequality between Pakistan’s elite and the general population. It reveals that a mere one percent of feudal families own over 22% of the farmland. Currently, the richest 0.2% of Pakistanis each own more than 400 acres. These feudal classes dominate politics, often occupying policy positions and granting themselves massive tax breaks on income and land revenue, along with subsidies on electricity, fertilizer, and water. This results in an annual “gift” of RS 370 billion from the government. Similar incentives are provided to other sectors, such as the corporate sector (RS 724 billion), traders (RS 348 billion), and high-net-worth individuals (RS 386 billion). Annually, the elite benefit from up to 2.66 trillion rupees—four times more than the money allocated for social protection for the most marginalized in society. Meanwhile, ordinary citizens face significant hardships: 3.8 million people in Pakistan experience food insecurity, 40% of children have stunted growth, and 50% suffer from anemia due to malnutrition. (Rule By Fear, 2021)[1]

The militarization of society is a natural consequence of this divide, where the primary mode of interaction between the masses and the elite becomes dehumanizing violence. The growing gulf poses a challenge to social stability and democracy. The country’s incorporation into the global imperialist system exacerbates this situation, pushing the economy further into the grip of international financial institutions through debt. This integration has further entrenched these inequalities. International financial institutions, such as the IMF, often impose conditions on loans that require austerity measures. These measures typically involve cutting public spending, privatizing state-owned enterprises, and liberalizing the economy. While these policies are meant to stabilize the economy and promote growth, they often result in increased poverty and inequality. The burden of these measures falls disproportionately on the poor, who lose access to essential services and face higher costs of living.

Dr. Miftah, a former finance minister of Pakistan, describes the country as a “One Percent Republic”—a society designed to benefit a few and perpetuate elite privileges. This perspective underscores the intimate connection between educational, political, and economic power within the state. The catchphrase “1% vs. the 99.9%” highlights the struggle against the billionaire class, which has hindered young people from achieving social mobility as they grapple with mounting debt and living expenses.

Liberalism for the rich has allowed Pakistan’s elites to create separate communities, schools, public spaces, hospitals, and even languages. These efforts to isolate themselves from the rest of society make them leaders of the most successful separatist movement in the country’s history. No ruling class willingly gives up its privileges out of a change of heart. While individuals may break ranks, a collective class suicide is unlikely. Only a new coalition powered by the forgotten and marginalized can challenge inequality and present a compelling vision for the future. Lessons can be learned from Latin America, where powerful coalitions have emerged to challenge elites and reject the US-imposed economic order. Leftist movements have won elections on anti-neoliberal platforms, including a schoolteacher in Peru, a student activist in Chile, and a union leader in Brazil, with Lula De Silva’s recent return to power. These movements advocate for economic sovereignty, wealth redistribution, and reestablishing a relationship between the state’s developmental objectives and the private sector. (Ammar Ali Jan, The News, 2022)[2]

The disparity between the rich and the poor continues to grow, creating a society that is increasingly divided and unstable. The rich receive substantial benefits and support from the state, while the poor are left to struggle with poverty, food insecurity, and lack of access to necessities. To address these inequalities, a coalition of the marginalized must rise to challenge the status quo and push for a fairer distribution of wealth and resources. Only through such a movement can we hope to achieve social cohesion and democratic progress.