Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Social And Civic Engagement: Building Community Or “Bowling Alone”?

Would Pakistan be experiencing the kind of crises—social, political, economic and one of identity[1]— that it is currently facing, if the country had better social and civic engagement? Would our democracy be more robust with more engagement by the community? These are rather complex questions to give a definitive answer to, but we have examples where extraordinary levels of people’s engagement have helped in developing a healthy community, and by implication a more vibrant democracy. It is premised that strong interpersonal sociability and associational life can create opportunities for people, foster a sense of efficacy, and constrain capture by any interest group.

Are people in Pakistan socially engaged or are they “bowling alone”? Bowling alone is an idea given by Putnam (2000)[2] in his study on the changing American behaviour over the decades. Putnam believed that Americans were becoming increasingly individualistic and disconnected from social structures — that is structures like clubs, associations, organisations, or bowling leagues. To him, more and more Americans were preferring to bowl alone instead of with others or in leagues.

Communities develop when there are opportunities for social and civic engagement to emerge. In the PIDE-BASICS Survey[3], we asked people if they were members of any club or organisation, and if they did any volunteer work. In case they were, we asked them about the nature of the club/organisation, and the kind of volunteerism they did. Based on this information, the current Note will see the trends for social and civic engagement for the four provinces and the three territories, and across regions, sex, age, and education and income levels.

Social Engagement through Membership of Any ‘Social Structure’

The social structure holds society together. Social roles, statuses, networks, organisations, groups and institutions are the major components of any social structure. In this BASICS Note, we are looking at the membership of any club or organisation as a means of social engagement for people. It may be clarified here that the referred club/organisation can be of any size, nature and level of formality.

____________

[1] See PIDE BASICS Notes, Number 3.

[2] Putnam, R. D., 2000, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[3] See PIDE BASICS Notes, Number 1, for details about the survey.

____________

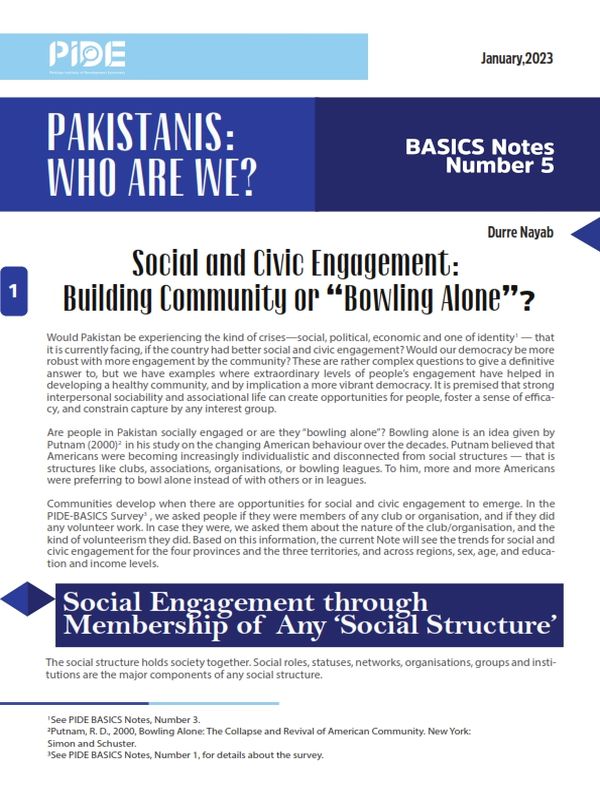

Membership by Province, Territory and Region

Figure 1 shows that only 3% of Pakistanis are a member of any club. The proportion remains generally low across the country, however:

- Slightly more people are a member of any club/organisation in urban Pakistan (4%) than in rural (2.5%).

- Among the four provinces, Balochistan has the largest proportion (6.5%) of the population that is a member of any club/organisation, followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (3.6%) and Sindh (3%). Punjab has the lowest proportion of 2.4%.

Gilgit Baltistan has the largest proportion (13.9%) of club/organisation members across all provinces, territories and regions.

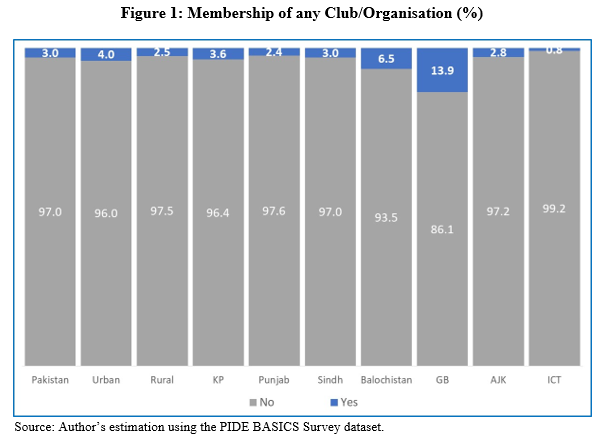

Membership by Age and Sex

Age and sex, as we have seen in previous BASICS Notes, have a major impact on all aspects of life, and this is true for membership of any club/organisation as well. Figure 2 shows the trends by age and sex, and we see that:

- Pakistani males (5%) have a higher rate of club/organisation membership than their female counterparts among whom only 1.1% have any form of membership.

- The rates remain generally low for all ages but is lowest among the young, i.e., those aged 15-24 year old.

- The rate is highest for males in age groups 45-59 and 60 years and above.

- For females the rates are extremely low, with those aged 25-34 years (1.9%) having a comparatively higher rate than those in other age groups.

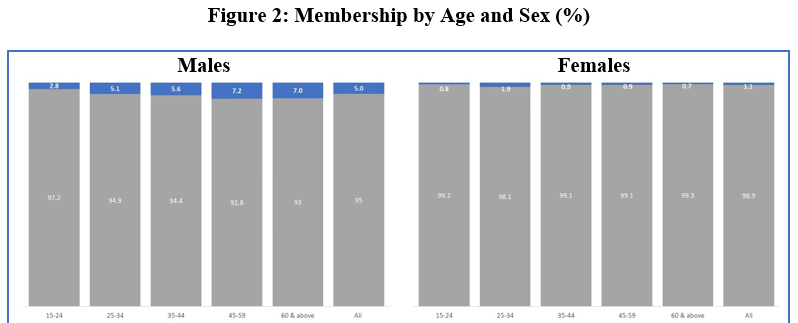

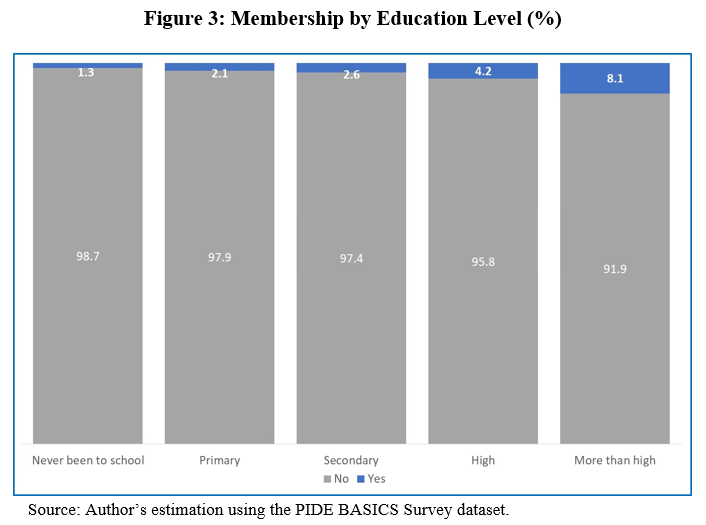

Membership by Education Level

Within the generally low level of club/organisation membership rates, education shows to have an impact on the proportion of people who are members. Figure 3 shows that:

- Pakistanis who have never been to school have the lowest rate of membership of any club/organisation.

- The membership rates show an increase as we go up the education ladder, with those having more than high education showing the highest rate (8.1%).

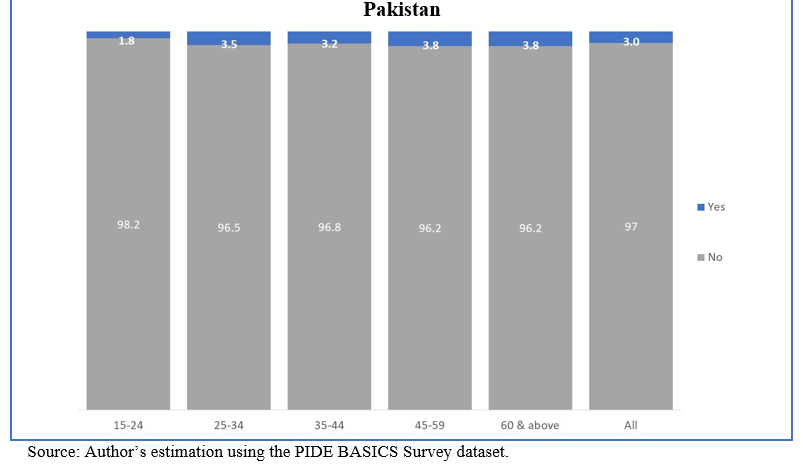

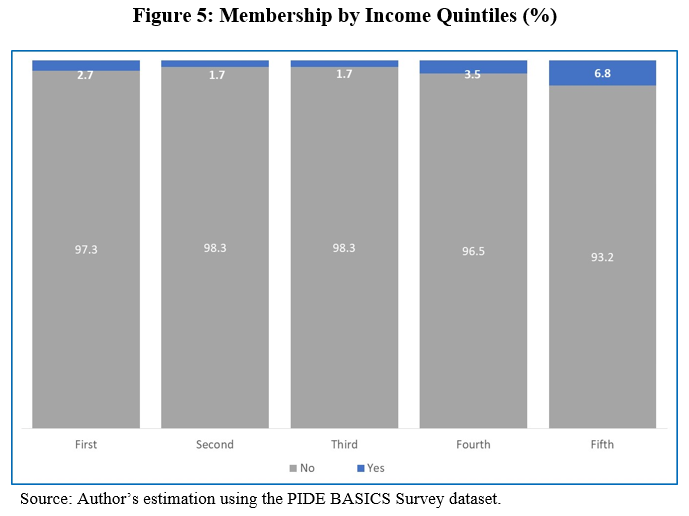

Membership by Income Level

Does an individual’s income level affect his engagement in any social structure? Figure 4 shows an interesting trend in this regard. We see that:

- The membership is lowest for the middle-income quintiles (quintiles two and three) – even lower than the first quintile.

- Income level has a positive effect on membership rates after the third quintile, and is highest for the richest quintile (6.8%).

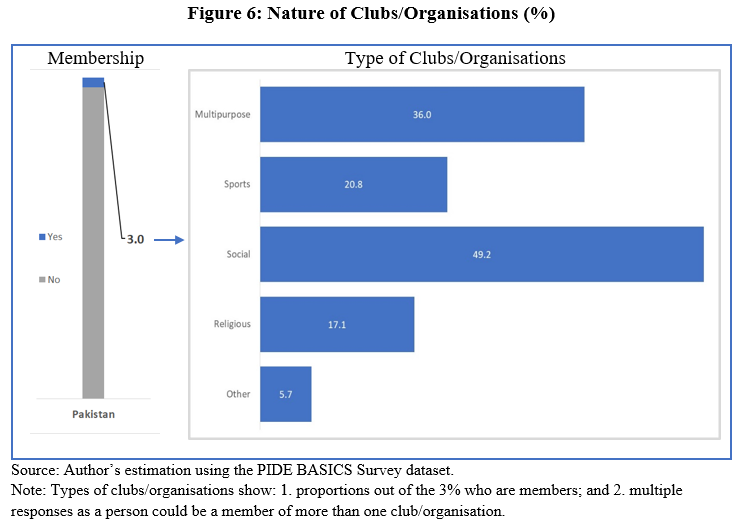

Nature of Clubs/Organisations

The above discussion shows that only 3% of the population of Pakistan aged 15 and above is a member of any social structure. Figure 6 shows the nature of these clubs/organisations. Since some people were members of more than one club/organisation, the figure below includes multiple responses.

We see from Figure 6, that:

- The clubs are mainly social, sports and religious in nature, with some being multipurpose. There were a few based on professions, neighbourhood and caste (included in the other category).

- Majority of those who are members are affiliated with structures serving social functions (49.2%), followed by multipurpose (36%), sports (20.8%) and religion (17.1%).

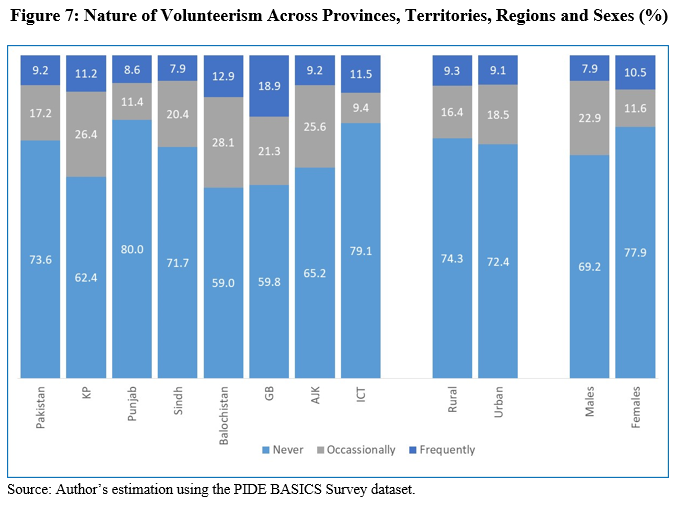

Civic Engagement

Civic engagement involves actions to make the quality of life in a community better. In the PIDE BASICS Survey, we gauged this through the involvement of people in voluntary work. As can be seen from Figure 7, we found that:

- At the national level, only 9.2% of the people did voluntary work on a frequent basis.

- As found in social engagement, civic engagement was stronger in Balochistan and GB as compared to other provinces and territories, respectively. GB had the highest rate across the country.

- Punjab had the highest proportion (80.1%) of those not involved in any kind of voluntary work.

- Not much difference was found between the urban and rural areas of the country.

- Males had a slightly higher rate of volunteerism than females, but not by much.

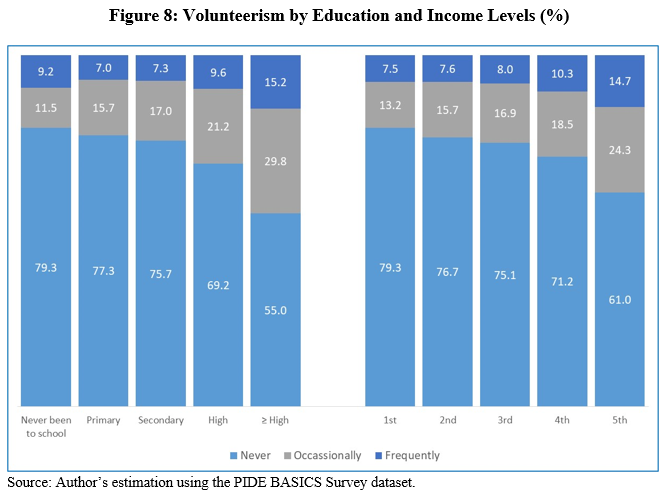

Figure 8 shows the trends of voluntary work across educational and income levels, and we find that:

- Volunteerism increases with increasing educational level, with those with higher or more education having the lowest proportion (55%) of those never being involved in voluntary work.

- Increased income levels are associated with a stronger involvement in voluntary work, as can be seen from the highest income level (fifth quintile) having the lowest proportion (61%) of those never engaged in voluntary work.

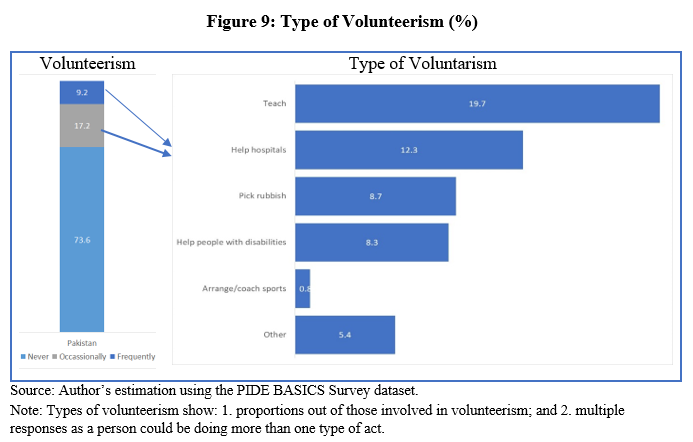

Those reporting to be involved in voluntary work, be it frequent or occasional, were asked the nature of the work they were doing. Those involved in more than one kind of work were allowed to give multiple responses. Figure 9 shows that:

- Teaching and mentoring others (19.7%) was the most common kind of volunteerism, followed by helping hospitals by providing provisions (12.3%), picking up rubbish and cleaning (8.7%), and helping people with disabilities (8.3%). A very small proportion (0.8%) was involved in coaching and arranging sports.

- Some other tasks (5.4%) that people were involved in included helping people out in the neighbourhood whenever help was needed, giving food to the needy, performing tasks at mosques and arranging/donating blood for patients.

| BASICS Note 5 shows that social and civic engagement, especially the prior, is not very strong in Pakistan. If people are not often engaged socially, how are they keeping themselves mentally and physically alive? Are there enough libraries and playgrounds/sporting facilities available for doing so?

Next BASICS Notes Number 6 Shaping Mind and Bodies: Do We Have the Facilities? |