Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

THE PAKISTAN DEVELOPMENT REVIEW

Rethinking the Development Model

The Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) has recently launched a framework of economic growth titled “The PIDE Reform Agenda for Accelerated and Sustained Growth”. The Reform Agenda points out that Pakistan has had a rough economic growth journey since independence due to intrinsic flaws in the development model which the country is still following. A rethinking of the development model and reconfiguring the role of the government is imperative to achieve a higher and sustainable growth that is indispensable for employment generation and debt sustainability.

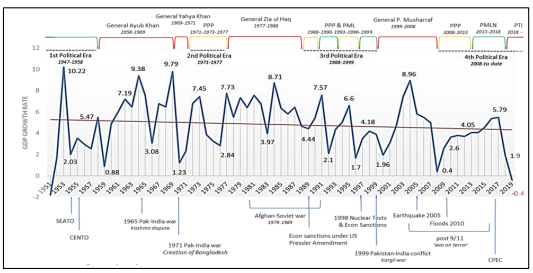

Over the last seventy-two years, the economic growth of Pakistan has remained volatile and has fluctuated widely. Likewise, the long-term growth shows a downward trend (see Figure below). Investment and productivity are the key determinants of economic growth, unfortunately, the dismal performance of Pakistan on both these fronts has contributed to the decline in long-term growth. The sporadic growth experience of Pakistan raises two fundamental questions, One, why Pakistan’s growth episodes are not sustained and two, what are the basic constraints to economic growth in Pakistan? This brief seeks to address these two issues.

Source: Faheem Jehangir Khan (2020).

Planning System and Development Model

The infrastructures, both physical and governance, which Pakistan inherited from the British in 1947 was limited and weak. The resources required to develop these infrastructures were too little[1] to fulfil the demand. Therefore, Pakistan had to rely heavily on the advice of the developed world and foreign aid to meet the physical infrastructure need and to fill and the capacity gap. Consequently, the Planning Commission was established in 1953 on the advice of the Harvard Advisory Group (HAG) to develop planning models backed by international consultants and development aid. The commission prepared the first 5-year development plan in 1955 by selecting high return-yielding investment projects and appropriating the investment requirements accordingly.

The Plan placed the government at the centre of the development plan and prioritised physical infrastructure and industrial base to modernise the economy. The development model based on this approach is dubbed the Haq/HAG Model in the development literature of Pakistan. The Haq/HAG model, which focuses on brick-and-mortar, was a great success initially and was also hailed as a model for economic planning of developing countries.

However, the flaws in the Haq/HAG framework, which prevails to date, began to appear once the foreign aid dried out. There are two main reasons for the ineffectiveness of the Haq/HAG model; (i) fiscal and budgetary constraints and (ii) the selection of the projects on a political basis instead of merit determined by well-defined criteria including economic and financial analysis. The fiscal and budgetary constraints replaced the Planning Commission with the Ministry of Finance as the key player in decision-making regarding development financing. While political and bureaucratic considerations undermined the ability to identify and appraise investment projects. Still, the Haq/HAG model of growth through aid-financed public sector infrastructural investment remains ingrained in Pakistan’s economic thought.

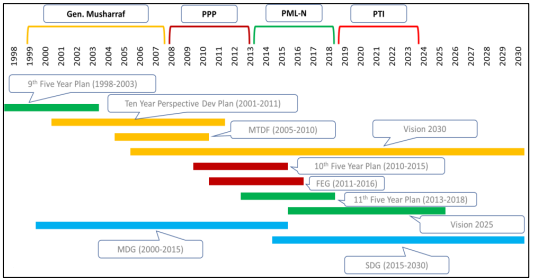

The figure below elaborates the fact that there are too many development plans with too little development. For instance, over the last two decades, Pakistan has tabled 10 major development plans, besides annual plans however not much implementation on any of the plans was observed, rather no effort seems to have been undertaken to evaluate the degree of implementation of the host of plans developed.

Source: Faheem Jehangir Khan (2020).

Evolution of Development Thinking

Haque, et al. (2020) classify the evolution of development thinking into five stages.

- (1) Aid: The initial development stage features excessive demand for physical infrastructure, and central planning is crucial. Since at this stage economies find investment and capital requirements daunting, they rely heavily on foreign aid and international consultants who pretend as development partners.

- (2) Poverty and Distribution: At the second stage, the development thinking concentrated on poverty reduction, and it was believed that economic growth can lead to poverty reduction. However, the link between the two is still unclear.

- (3) Structural Adjustment: Many developing countries were facing macroeconomic imbalances due to government interventions. These imbalances not only deaccelerated the growth process but also impede the poverty reduction programs. Ultimately, it was realised that economic liberalisation is critical, and market forces are the main drivers of growth. Thus, structural adjustment programs were initiated to reduce the role of the government in the economy.

- (4) Reform, Institutions, and Governance: At this stage, the development thinking moved beyond traditional growth theories. Institutions and governance emerged as the key determinants for investment, and technological development. Next, the improvements in quality of investment and technology contributed to growth and welfare.

- (5) Results Base: Now the new norm is to set detailed development targets—MDGs and SDGs are now accepted across developing countries as goals.

Pakistan stands somewhere between stage 1 (developing infrastructure and central planning) and stage 3 (structural adjustment). The policymakers are still obsessed with foreign funding-based infrastructure projects. Moreover, the progress on the structural adjustment front has virtually halted, and the government still has a massive footprint in the economy. The shift from stage 2 (poverty reduction) to stage 3 is not possible without the disentangling of policy-making from political interference and rethinking the architecture of the policy-making.

Shift on Growth Paradigm: Need of the Hour

The success stories of Europe and the United States during the industrial revolution provide basic principles of development policies. Many countries, learning from these principles, have achieved remarkable development in our lifetime. These key principles can be summarised as follows;

- Competitive and open markets are vital, so let the market forces define the winners and losers.

- The role of the government is to ensure the smooth functioning of markets by providing market rules and regulations. The government also acts as an empire to regulate fair play, allowing winners and losers to emerge without keeping alive obsolete industry through subsidy and protection (North, 1991).

- Research and new ideas are compulsory for innovation, which require an open and tolerant society. It also falls under the mandate of the state to develop an inclusive society, Romer (1990); Aghion (1992).

- The culture of competition, discipline, and risk-taking must be developed so that entrepreneurship and opportunities abound McCloskey, (2013).

- Contemporary economic growth literature considers economic governance and human capital to be the key determinants of growth, Ward (2011) & World Bank (1993).

Hence, the drivers of growth that have been identified from the growth experiences of the success stories are innovation, productivity, and entrepreneurship [see, Lucas (1988) & Romer (1990)]. To generate these driving forces, the role of the government is important—growth acceleration requires inclusive institutions that are responsive to ideas, innovation, and entrepreneurship, Acemoglu & Robinson (2010).

However, the Haq/HAG model based on the accumulation of physical capital does not encompass the growth principles stated above. As a result, there is little scope for innovation, increasing productivity, and facilitating entrepreneurship. The need of the hour is to rethink our development model, taking the lead from the growth principles referred to above. We have to redefine the role of government, markets, civil society, and academia. It is in this spirit that the PIDE Reform Agenda emphasises that the growth generator in the modern era is not the government but cities, asset classes, commodities, products, firms, and people with the government serving as an enabler.

The recipe for growth is long known and built on the above principles. The salient features of the recipe are: give the vibrant young people quality education, new ideas, and high ideals; strive for institutions that support free and fair markets; create a professional, well trained civil service; achieve economies of scale through a large domestic market and open up for trade and investment; and keep public spending on infrastructure and social sectors limited and focused only to critical and essential projects, Buiter & Rahbari (2011). Recent technological developments have added to this list the will and effort to embrace technology and ensure high-speed internet for all.

Now, the typical variables such as investment and savings are regarded as endogenous to the system. This implies that we must look for factors that allow space and freedom to invest productively (FEG, 2011). The PIDE Reform Agenda, therefore, recommends governance, judicial and regulatory reforms that would remove entry barriers for entrepreneurial activity, facilitate the development of vibrant and competitive markets, and would provide a level playing field to all.

REFERENCES

Acemogly, D. & Robinson, J. (2010). The role of institutions in growth and development. Review of Economics and Institutions, 1(2), 1–33.

Aghion, P. & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351.

Buiter, W. & Rahbari, E. (2011). Global growth generators: Moving beyond emerging markets and BRIC. Citi-Group Global, Global Economics View.

Haque, N. U. (2011). Framework for economic growth. Islamabad: Planning Commission of Pakistan.

Haque, N. U., Hanid, M., Ishtiaq, N. & Gray, J. (2020). Doing development better. Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22, 3–42.

McCloskey, D. N. (2013). The great enrichment continues. Current History, Nov. 2013, 323–25.

North, D. (1991). Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 71–102.

Ward, K. (2011). The world in 2050; Quantifying the shift in the global economy. HSBC Global Research, Global Economics.

World Bank (1993). The East Asian miracle: Economic growth and public policy. Policy Research Report.

[1] The domestic saving during 1950 was merely 2 percent and investment stood around 4 percent of GDP during 1950, see Haque, et al. (2018).

Ahmed Waqar Qasim