Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Making Sense of Remittance Growth in the Time of COVID-19

The Year 2020 and Migrant Remittances

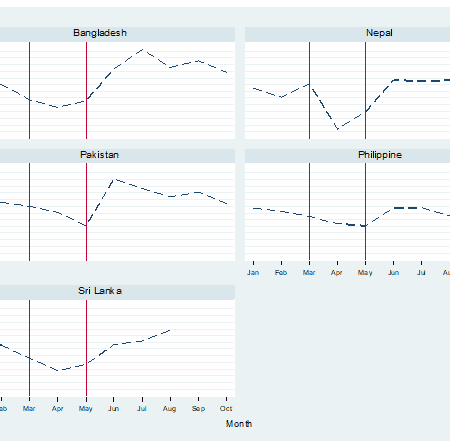

The year 2020 has ended, leaving a trail of death and destruction. One shining star for the economies of developing countries like Pakistan during this annus horribilis though has been migrant remittances. Pakistan’s remittance inflows stayed north of USD 2 billion for six consecutive months, despite sluggish economic conditions in host countries. This has helped the country post a 17-year high current account surplus. During the June – November 2020 period, remittances to the country grew by a remarkable 30.5 percent. Though less spectacular than Bangladesh’s 40 percent growth, Pakistan’s numbers are better than most other major recipients in the region. Remittances to Nepal grew by 10 percent (June – September), Philippines by 5 percent (June – September) and Sri Lanka by 16 percent (June – August).

Note: (% change in remittances compared with the same month in 2019)

Source: Central Banks of the respective countries

The Early Days of the Pandemic

In the early days of the pandemic, remittances fell sharply. April numbers for Nepal were less than half those a year ago (58 percent). Sri Lanka and Bangladesh too witnessed decrease of 32 percent and 23 percent respectively. Though remittances to Pakistan resisted in April, the month of May saw a decrease of 19 percent. When in June, remittances surged by a mind-boggling 51 percent, it was thought that these were repatriated savings of Pakistani workers who were relocating after losing jobs in the Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC) and elsewhere.

The alternative explanation was that these flows corresponded to pent-up transactions accumulated during lockdown months of March, April and May. But remittances maintained their unprecedented levels, reaching the highest recorded level of USD 2.7 billion in July; challenging this assertion.

So what could explain Pakistan’s stellar performance? Here are a few possible reasons.

Money Transfer Channels

One explanation that is often cited in this regard is the growing popularity of formal money transfer channels among Pakistani migrants. This argument indeed holds some merit.

A non-negligible share of informal remittances are carried back home by hand. This channel was disturbed due to Covid-related international travel limitations. Increasing curbs on the informal Hundi payment system to comply with Financial Action Task Force requirements may also have contributed in the increasing number of formal financial transactions. Besides, the State Bank and the government have over the past two years made sustained efforts to lower the cost of remitting to Pakistan. The minimum amount for availing inexpensive bank transfer facility under the Pakistan Remittance Initiative (PRI) was lowered to USD 200. As a result of these factors, the volume of remittances received through official channels has grown even though the total amount of dollars entering the country may remain the same.

Informal Channels

A look at inflows from Pakistan’s top migrant destinations may shed some light on this matter: During the past six months (June – November), remittances from all the major source countries showed an increase with the exception of Malaysia from where remittances fell by 52 percent. Remittances from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan’s biggest migrant destination, rose by a strong 39 percent. However, inflows from the UAE and other GCC countries (Kuwait, Qatar, Oman and Bahrain) increased by a more modest 13 percent and 15 percent respectively.

Restrictions on Hundi should influence the remittance behavior of migrants in the GCC economies more so than in the West. The majority of Pakistanis in these countries are semi- or un-skilled workers financially supporting their families back home through frequent transfers. Hundi has historically been the channel of choice for their small amounts of remittances. They also carry their savings back home when visiting their families. Air travel serves as an important channel for remittance flows given shorter travel time and greater frequency of visits of workers living in these countries.

Increased Investment from Overseas Pakistanis

Another reason, and which may help understand the increase in remittances from the Western countries better, is the increase in investments made by overseas Pakistanis. The inflows from the Western economies has grown more substantially: remittances from the United States of America grew 27 percent during the June – November period, those from the United Kingdom grew 49 percent, and those from the countries of the European Union grew 55 percent. Prolonged lockdowns and related economic weakness of these countries has made investing in developing countries like Pakistan a more attractive proposition.

The amount invested in The State Bank’s Roshan Pakistan digital accounts launched in September has crossed USD 200 million. It is also reflects greater interest in the construction and real-estate sector shown by overseas Pakistanis. Real estate is one of the foremost investments that migrants from developing countries make in their home country, as it provides them a way to secure their savings. Previous research in Pakistan has shown that between one third to half of remitted amounts is used to purchasing land or constructing houses.

Diversity of Remittances Sources

Yet another factor, that distinguishes the remittance inflows to Pakistan and Asian countries like Bangladesh, India, the Philippines and Sri Lanka from those to other major recipients such as Mexico, Egypt, Morocco and Tajikistan, and which may explain their sustained rise, is the diversity of their sources. The latter group of countries principally depend on one country or region for the bulk of their remittances: the USA for Mexico and other Latin American countries, the GCC countries for Egypt and Jordan, the Russian Federation for Tajikistan and other former Soviet republics, and the European Union for Morocco, Tunisia and East European countries. In contrast, Pakistan’s migration profile, and the subsequent remittance portfolio, is diversified, with no source country accounting for over 25 percent of the country’s remittances. The GCC countries together accounted for 54 percent of the inflows in 2019, followed by Europe including the UK (18 percent), North America (16 percent) and Australasia (7 percent). This diversity mitigates possible downside effects of the host-country business cycles, and reduces the country’s dependence on one particular source.

Worker Migration Abroad

Finally, the increase in remittances may be a direct mechanical consequence of the growing number of Pakistani workers going abroad. In the recent years, labour is exploring new markets such as Japan and other Asian countries, thanks to the government signing Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) with these countries. After three years of falling numbers, the number of Pakistani workers going abroad grew spectacularly in 2019, showing an increase of 63 percent. Though an unknown number of Pakistanis are leaving for Western countries, the number of registered workers going to the GCC countries rose sharply.

The numbers of departures for Saudi Arabia, Pakistan’s biggest migrant destination, increased from 100,910 in 2018 to 332,713 in 2019. The government has managed to send a record number of nearly a million Pakistanis abroad during the past two years. More financial transactions are being made in Pakistani banks, reflecting this increase.

This source of rising remittance inflows may now be in danger: Covid-related travel restrictions and reduced demand for foreign workers arising from the global economic slowdown during 2020 are beginning to hit the number of Pakistani workers going abroad. This could seriously affect the potential for increases in remittances in the near term.

Download full PDF