Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Gas Crisis In Pakistan

Afia Malik and Usman Ahmad[1]

Senior Research Economists

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

PREFACE

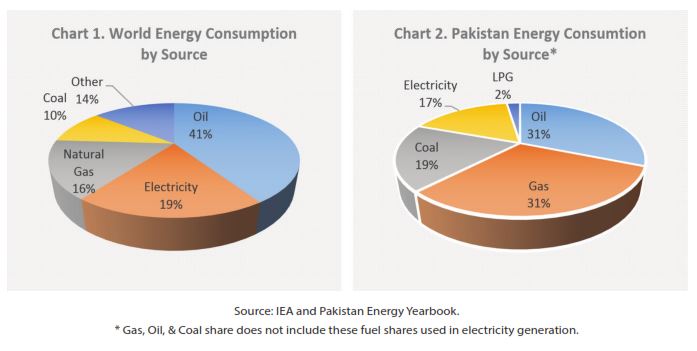

Gas is the third-largest energy source consumed around the world. Pakistan has less than a 1 per cent share in world gas consumption. It meets its energy demand through imported and indigenous resources in the ratio of 44:56. Natural gas and imported LNG contribute more than 40 per cent to the country’s current energy mix, including gas resources used in electricity generation. In recent years, the demand for gas has increased rapidly in Pakistan. However, gas exploration and production have declined, and the LNG operational and regulatory framework is weak, leading to a nationwide shortage and increased supply costs.

_________

[1] This Knowledge Brief builds on information shared in PIDE Webinar on ‘The Gas System in Pakistan’ held dated October 24, 2020. Our special thanks to Dr Nadeem ul Haque for the idea and for sharing valuable insights on the subject.

PAKISTAN NATURAL GAS SECTOR

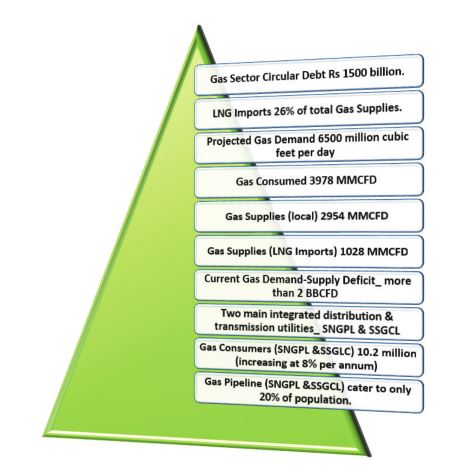

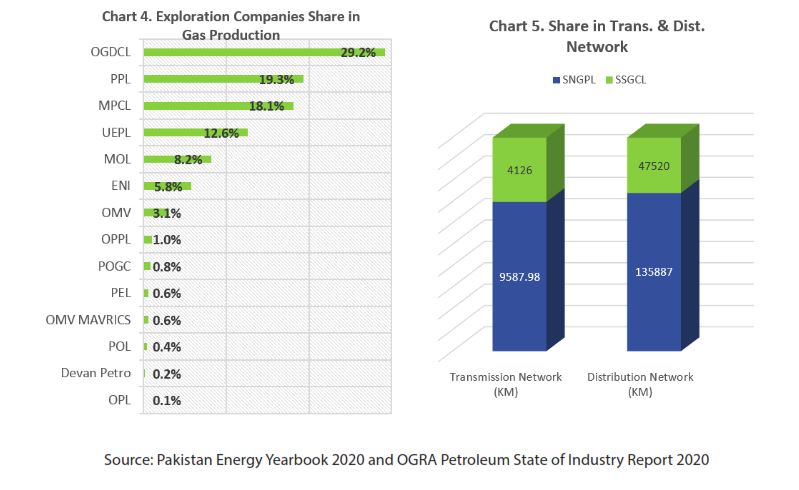

In the upstream, 15 gas exploration and production companies work in 55 gas fields spread throughout the country. The gas distribution and transmission are mainly owned and operated by two state-owned companies _ Sui Northern Gas Pipeline Limited (SNGPL) and Sui Southern Gas Company Limited (SSGCL). A few independent pipelines from Mari and Uch also supply gas to nearby power and fertilizer plants. SNGPL and SSGCL are listed companies with the majority of shares owned by the government.

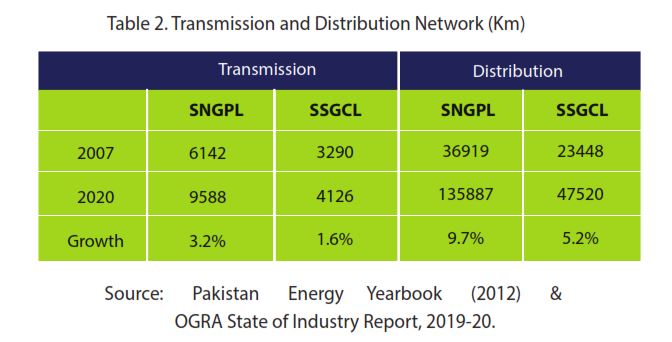

After the colossal gas discovery in Sui in 1952, the GOP started developing a gas transmission and distribution network. The transmission network (13714Km) and distribution network (183407Km) are spread across four provinces’ main urban areas. The gas exploration/production industry and gas distribution/transmission industry lack competition in Pakistan.

GAS SECTOR CHALLENGES

The sustained growth in gas production in the early years made authorities complacent, and they encouraged consumption_ and gave connections to everyone. Gas tariff methodology also enabled capital investments to expand the transmission and distribution (T & D) network (Malik, 2021).

- Pakistan is the most gas-intense country in the world. Over the years, the gas has been used quite ine ectually.

- Cross-subsidization across sectors encouraged ine cient use, and it continues.

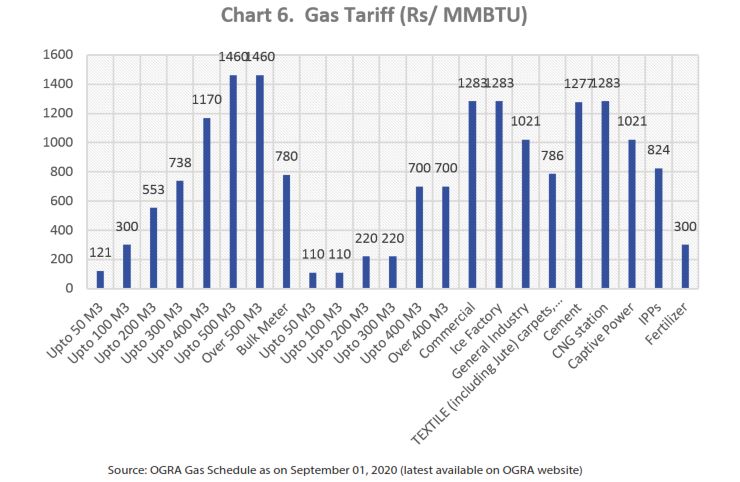

Household consumers have a share of around 50 per cent of total gas consumption, and the percentage of fertilizer plants (feedstock) is about 12%. The majority groups/ slabs in these two categories are charged a low price (much below the costs) than all other consumer types_ incentivizing inefficient use. Other consumer categories are charged a price higher than the actual cost.

Although 78% of households have no access to natural gas in Pakistan, natural gas consumption in the domestic sector has grown by about 11% over the years_ maximum growth among all the sectors. Supplying gas to households requires significant investments. The cost of gas supply to households is much higher than the cost of supply to the industry or power sector. In our gas prioritization policies (over the years), this has not been reflected, leading to a shortage of gas supplies.

- Gas allocation policy has remained based on political priorities rather than on the objective of maximizing

value addition. - Low gas prices and ine cient gas allocations have encouraged higher demands.

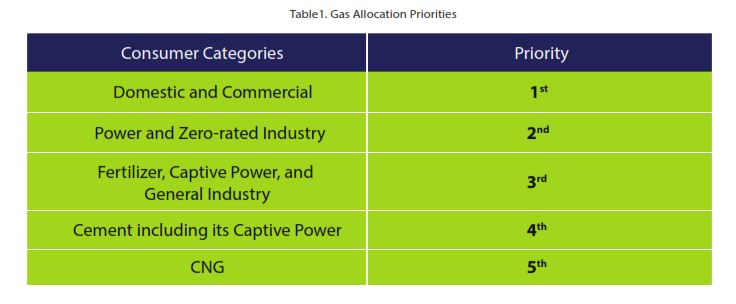

In 2005, the government announced Natural Gas Allocation and Management Policy, which was revised later few times. The latest revision was in 2018. Different sectors have been prioritized as in Table 1.

In most countries (mainly developed countries), a single energy source is provided at the domestic and commercial levels.

- In Pakistan, both power and gas are supplied at the household level. Providing two types of infrastructure at the domestic level is costly and encourages inefficiencies in the supply chain.

Single-pass gas geysers dominate household gas consumption bills (almost 80%). These geysers are incredibly inefficient (efficiency level less than 30%). At the same time, very few pay the actual cost in the household category as most slabs are cross-subsidized (Chart 6). In comparison, the industry can achieve supply-side efficiencies up to 90%. The industry’s gas tariffs are relatively high, in addition to gas outages. Expensive gas makes goods’ costs high and reduces local and global competitiveness (Farid, 2021).

Subsidized gas supply to fertilizer is for food security and protecting small farmers. But evidence suggests fertilizer prices are not always below the imported fertilizer costs. Local fertilizer manufacturers are making enormous profits (Raftaar, 2016). While the reduced supply of gas to power or high tariffs for the power sector sometimes aggravates the power shortage. It increases power generation costs, adversely affecting the economy (Malik, 2021).

Likewise, despite the forecast of a rising demand-supply gap, in FY2006, when international oil prices were rising, GOP promoted CNG to replace motor gasoline by keeping its prices substantially lower than motor gasoline. It was a government policy of maintaining a substantial difference in the price of petrol and CNG to promote the CNG industry in the country, despite the declining natural gas resources. Policymakers/ regulators failed to perceive the gap arising from the oil to gas shift.

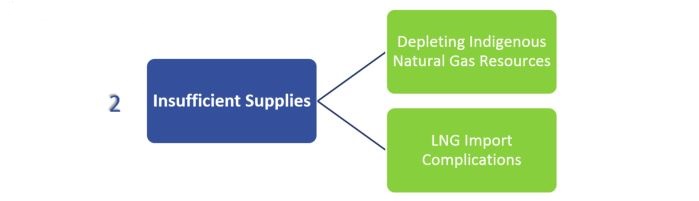

With 30.6 billion cubic meters of natural gas, Pakistan shares 0.8 % of global production (BP, 2021). There is a sharp increase in gas demand in Pakistan, but due to the inefficient distribution of natural gas resources, Pakistan has been facing a colossal gas shortfall.

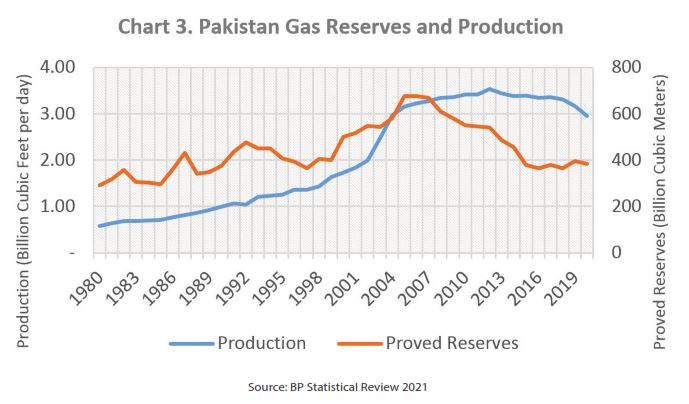

- With no significant gas discoveries in recent years, gas production has started decreasing after reaching a peak in FY2012.

- No significant addition, proven gas reserves are also declining (Chart 3).

- Basin studies suggest a total gas resource potential of 282 trillion cubic feet (Abbasi, 2018) [2].

- There are only four exploratory wells per 1000 Sq. KM, three times less than the world average (Sattar, 2020).

OGDCL predicts that Pakistan’s indigenous oil reserves will be exhausted by 2025. Current reserves will last a maximum of 15 years if demand is capped at present-day gas levels by 2030 (Sattar, 2020).

Maintaining all operations or controlling all activities by the GOP create inadequacies, costing welfare and economic loss. Pakistan’s upstream sector has become unattractive for foreign investment because of the factors listed in Box 1. A few years back, there were 22 foreign companies in exploration & production activities, but we are now left with only 3 (Sattar, 2020).

__________

[2] According to Sattar (2020), only 8% of total gas potential (1400TCF) has been discovered.

__________

Box 1. Factors Responsible for Low Exploration Activities

For local companies with state ownership

Source: Malik (2021) & Sattar (2020) |

Large areas in the country remain unexplored due to security concerns and the law-and-order situation. For instance, Baluchistan’s Pishin basin is considered a valuable block. However, no exploration activity in this basin because of the law-and-order problem. Likewise, the well-head price policy, the structure of the bidding process for the blocks, and the government’s role in state-run companies are discouraging companies. Political instability and related policy uncertainty is also not an incentive for investors.

Companies are also exploiting; they bid for blocks but do not start work on them. Government has clauses in the contract that can penalize or take back blocks but has never really enforced these and has not taken one back in decades. The attitude of companies in the upstream sector explains regulatory weaknesses in the oil and gas sector.

LNG Import Complications

Box 2. Issues in LNG Imports

The spot LNG market exhibits more volatility than other fuels; prices can move substantially in either direction when the LNG vessel arrives. Source: SBP, 2021 |

Since FY 2015, Pakistan has been importing LNG to meet domestic gas shortages. Two state-owned companies, Pakistan State Oil (PSO) and Pakistan LNG Limited (PLL), are importing LNG. PSO has signed a long-term contract (15 years) with Qatar. PLL has relatively short-term contracts with Gunvor and Shell[3]. LNG imported by PSO and PLL is re-gasified at the Engro Elengy Terminal Limited (EETL) and PGP Consortium Limited (PGPCL), respectively[4].

Rising LNG price trends in the global energy market are creating problems in securing LNG supplies in Pakistan[5]. The LNG price shock is expected to continue over the coming several years due to global developments in the wake of the Ukraine War.

________

[3] Pakistan recently signed another G2G deal with Qatar to import 200 MMCFD of LNG from 2022 onwards at an applicable Brent slope of 10.2%. This would increase to 400 MMCFD after three years.

[4] EETL has a peak capacity of 690 million cubic feet per day (MMCFD) for re-gasification. PGPCL has a peak re-gasification capacity of 750 MMCFD (OGRA, 2020).

[5] Spot Asia LNG rates are three times higher than normal for this time of year (Hasan, 2022).

________

Substantial government involvement across the LNG supply chain, the distorted subsidy structure[6], and political preference for the subsidized category make the actual recovery of LNG

costs difficult[7]. Like exploration activities, the current operational, regulatory, and procedural challenges have more to do with government control and exclusive involvement in the business. How much to import LNG in the spot market or through a long-term contract is unclear.

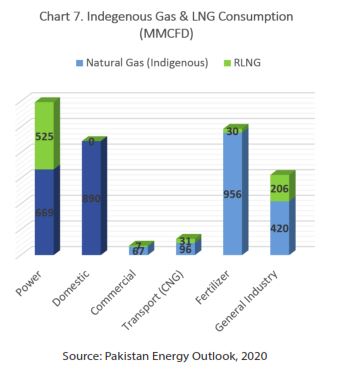

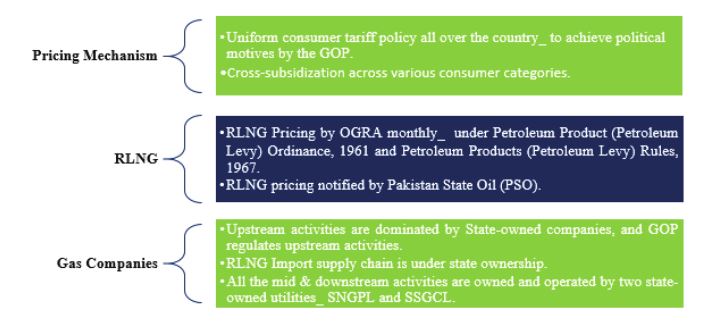

There is a dual gas pricing system; local gas and RLNG are priced independently (Malik, 2021). The Senate of Pakistan in February 2022 approved the Weighted Average Cost of Gas (WACOG) bill. Under WACOG, all gas sources, including Re-gasified Liquefied Natural Gas (RLNG) and local gas, will be pooled in, and a weighted average cost will be taken for gas purchase. But a month later, the bill was challenged in court, and a stay was granted.

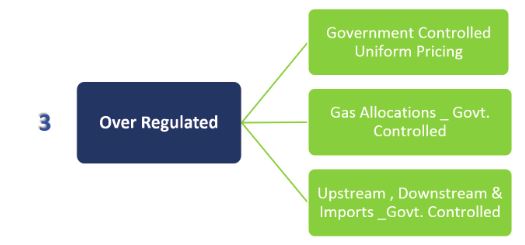

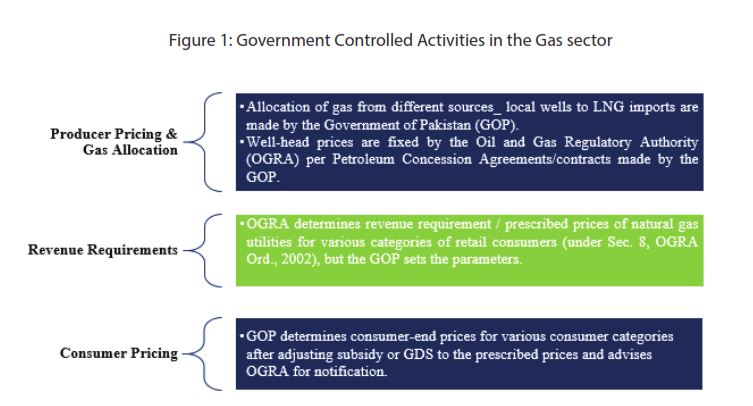

All the activities in the gas sector in Pakistan, directly or indirectly, are under government control (Figure 1).

An independent regulator was established in 2002 to regulate mid and downstream activities. Still, it remained hostage to government decisions because of the extensive state presence in all activities in the supply chain. The OGRA law allows too much mandatory government involvement in the current oil and gas regulatory system. That has made the regulator powerless[8].

Government interference in service providers’ affairs has led to cross-subsidy and an overall deficit in the gas sector. The circular debt in the gas sector has crossed Rs 1.5 trillion, contributed by both the utilities SNGPL and SSGCL. The gas sector deficit is increasing because of the differential in consumer prices and the determined revenue requirements (ICAP, 2020).

Government irregularities in regulatory frameworks and poor policy formulation are hindering sectoral growth and creating inefficiencies in the supply chain. Politically influenced allocations and monopolistic business operations are all bottlenecks (Sattar, 2020).

________

[6] Pakistan featured in the top 10 countries providing the most subsidies to the natural gas sector in 2019, with the level close to the one observed in the gas-exporting countries. The subsidy amount was around US$ 1,750 million in real terms compared to US$ 873 million in India and US$ 824 million in Bangladesh.

[7] Low quality appliances consume more gas than national or international set standards. Consuming LNG in these products is criminal (Sattar, 2020).

[8] Cited from OGRA Evaluation, Effectiveness of Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (Malik, Unpublished).

________

Apart from issuing licenses, there is no effective role of OGRA in regulating gas sector prices. The Authority is only computing prices based on already set parameters by the government. Due to the gigantic state presence in the gas sector, the enforcement of performance standards by OGRA has also remained weak.

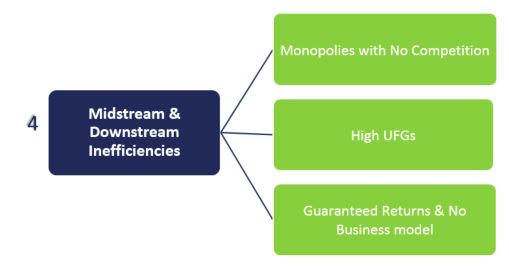

The objective behind OGRA was to foster competition and increase private investment and ownership in the midstream and downstream petroleum industry. But the privilege state monopolies have enjoyed has not allowed this to happen.

Unlike many gas markets, they do not own gas molecules; therefore, they are not in competition with gas producers. They buy gas from the well-head, transport and distribute gas under a 10–25-year contract at prices determined when E &P concessions were awarded. Transmission & distribution fees are relatively modest compared to gas markets like Brazil (Malik, 2021).

- Financial returns to these companies are linked to the transmission and distribution assets (network).

- Tariff setting rewards capital investment in network expansion over pipeline maintenance.

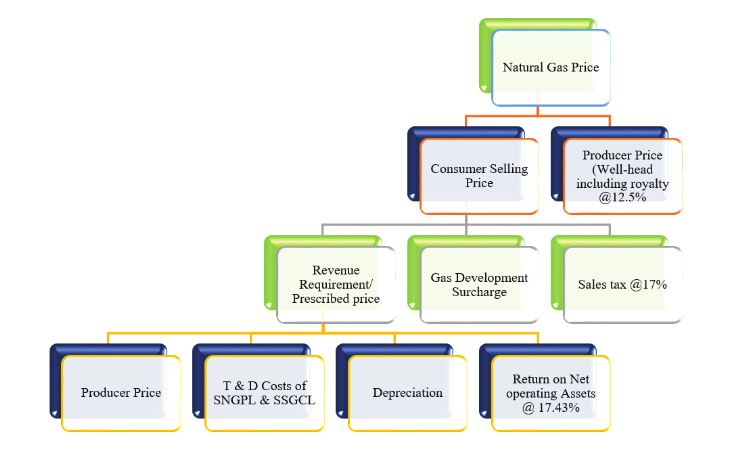

The calculation of the revenue requirements (in tariffs) incentivizes network expansion over pipeline maintenance. New connections increase the utility’s fixed assets, and the companies are guaranteed a market-based return of 17.43% on their net operating fixed assets (OGRA, 2020).

Figure 2: Consumer Gas Price Mechanism (Cost-Plus)

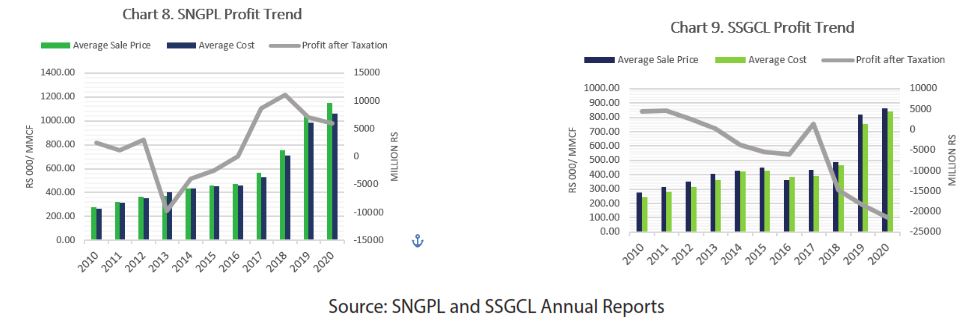

Ensuring reliable and high-quality uninterrupted natural gas supply and efficient services is one of the critical aspects of the regulatory process. The gas distribution companies must maintain adequate pressure in the transmission pipelines and distribution networks and upgrade the system where necessary to ensure supply of contractual volume and pressure to its consumers. Gas resources are depleting, but these monopolies are expanding their transmission and distribution networks to maximize their financial returns (Table 2). These companies, especially SNGPL, have earned enormous profits over the years (Charts 8 & 9).

In both utilities, mismanagement and irregularities have affected their operational performance. Though private entities own 40% or more of their shares, these companies have no business model. There is no regulatory mechanism to link their financial returns to their operational efficiency; UFGs in these companies are seven times of world average.

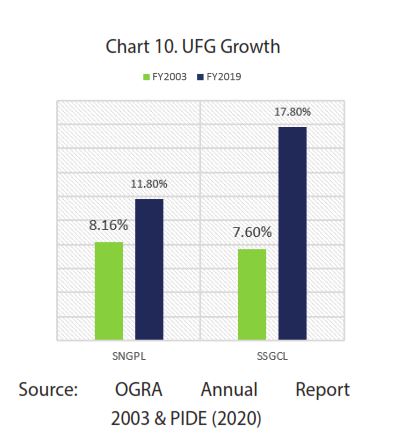

Underground leakage from ageing pipelines, poor maintenance, measurement errors, wrong billing, law & order, and theft have contributed significantly to Pakistan’s unaccounted-for gas (UFG) (KPMG, 2017). The two integrated companies, SNGPL and SSGC, are over-regulated monopolies with no incentive to improve their inefficiencies and service delivery. Against the OGRA allowance of UFG at 4.5 %, the gas losses in these companies remained relatively high. After 2017, this allowance increased to 7% and 8.5% for SNGPL and SSGCL to compensate for declining profits.

Box 3. International UFG Allowances

Source: KPMG, 2017 |

Regarding the return on assets, the mechanism was adopted some thirty years back when the Asian Development Bank and World Bank lent both companies for their infrastructure development and wanted a guaranteed return. Now this guaranteed return is disincentivizing efficiency. No efforts are underway to get away from this mechanism.

Box 4. Gas Market Reform_ Lessons from Japan and South Korea

Before Reforms

After Restructuring

Source: Choi (2019) & SBP (2021) |

Way Forward

- Prioritize exploration activities for relying minimum on LNG imports_ correct well-head prices and minimize government interference.

- A progressive and market-based exploration policy is needed.

- Pakistan should de-regulate the natural gas sector and liberalize the pricing structure. Market-based pricing system will also curtail the misuse of gas.

- For LNG imports, incentivize third-party access_ increased involvement of the private sector in the LNG supply chain happening in mature LNG markets like Japan, South Korea and even in India[9]. Higher private sector participation in these countries facilitates cheaper fuel availability, smooth procurement processes and allow market-based price discovery (SBP, 2021).

- To maximize returns from private sector involvement and guarantee the sustainability of the natural gas sector, it is essential to first solve the profound structural and operational challenges.

- Without rationalizing the subsidy structure, the financial viability of the natural gas sector is difficult to achieve. The tariff must be set on a cost-of-service basis for a reliable and sustainable gas sector.

- WACOG or any other price pooling formula does not seem politically feasible. The government must begin passing LNG costs to the consumers. Otherwise, the circular debt will continue to inflate as in the power sector.

- Gas allocation to sectors should be from a growth perspective and not based on political decisions. Energy efficiency legislation and strict implementation in all sectors are compulsory.

- Restructuring of gas utilities is required to improve their operational and managerial efficiency. Unbundling these monopolies between ‘pipeline’ and ‘retail’ is inevitable before allowing for other private participants in the ‘pipeline’ and ‘retail’ business.

- To improve management and administration in SNGPL and SSGC, slicing them into smaller units may also help.

- It’s high time to get rid of guaranteed returns based on network expansion. Companies must have a business model to earn profits from operational efficiency.

- UFGs can be reduced by strictly monitoring the supply chain and putting the cost of the losses on the distribution companies, which will ultimately ensure their efficiency.

- All gas companies should operate commercially without any political interference by any government.

- Government should limit its role to policy making and effective legislation for market liberalization.

There should be a single autonomous regulatory authority for upstream, midstream, and downstream activities. But the regulator must have powers and capacity to monitor the sector effectively and ensure market development.

_______

[9] India recently has de-regulated its natural gas sector.

_______

References

- Choi, J. (2019). Developing Free and Open Markets: Gas Market Reform in Japan and South Korea. NBR Special Report 81, https://www.nbr.org/

- Farid, N. R. (2021) Gas Allocation Policy: A Skewed Priority and a Vicious Cycle. Available at https://www.brecorder.com/

- Hasan, M. (2022) Pakistan Takes Another Shot at LNG Import. The News, June 17, 2022.

- ICAP (2020), “Oil & Gas Sector – Exploration, Production & Distribution: Surviving the Crisis & Entering the New Normal”, Post Webinar Paper, Institute of Charted Accountants of Pakistan.

- KPMG (2017). Oil & Gas Regulatory Authority Un accounted for Gas – Study. Final Report July 2017. Karachi: Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler.

- Malik, A. (2021) Gas and Petroleum Market Structure and Pricing. PIDE Monograph Series, 2021.

- PIDE (2020). The gas system in Pakistan. PIDE Webinar, October 24, 2020.

- Raftaar (2016). Gas report. (Report No. R1502), Consortium of Development Policy Research (CDPR), https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Gas-Reportmerged-final.pdf

- Sattar, S. (2020) Gas Sector in Pakistan, presented in PIDE Webinar on ‘The Gas System in Pakistan’ October 24, 2020.

- SBP (2021) LNG-Attaining Sustainability Through Deregulation and Structural reforms, State Bank of Pakistan, Second Quarterly Report, 2020-21.