Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

THE PAKISTAN DEVELOPMENT REVIEW

Invest in Future: Prioritising Youth Family Planning

Dividend of our much-touted youth bulge will remain a pipedream unless our policy makers realise the need for investing in the health, education, and general wellbeing of the young. Our young population is at a greater risk than adults when using contraceptive services. This risk results from a lack of early education in human reproductive system as well as the cultural taboos surrounding the subject. Affordability, accessibility, and knowledge of contraception are inadequate for young women and couples who would want to space pregnancies. Individuals’ reproductive intentions remain uninformed by critical awareness that swells the number of unintended pregnancies, further aggravated by hazardous unprofessionally administered abortions.

One-third of Young Married Women Have a Desire to Use Contraception

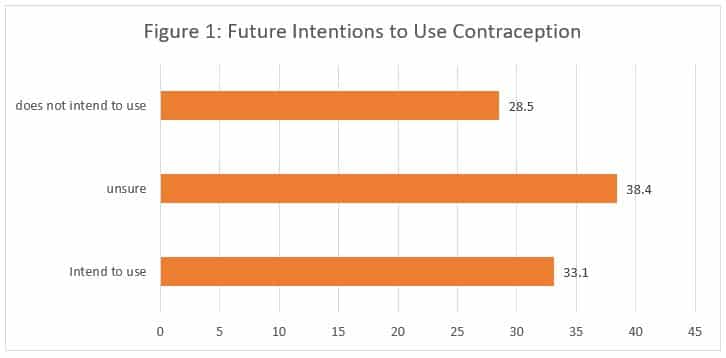

There are misconceptions that family planning is for older or married women, despite the fact that many adolescent girls are sexually active. Nearly one third of the young married women, aged 15–19, have a desire to use contraception but are not currently using any contraceptive methods in Pakistan.

Early Initiation of Childbearing is Linked to Education, or Lack of it.

Universally, early childbearing before age 18 is associated with many socio-demographic and economic risk factors for young women. For instance, having a child during teenage has adverse consequences for both mother and child’s health. Similarly, women who marry before they are 18 are more likely to drop out of school and are less likely to work.

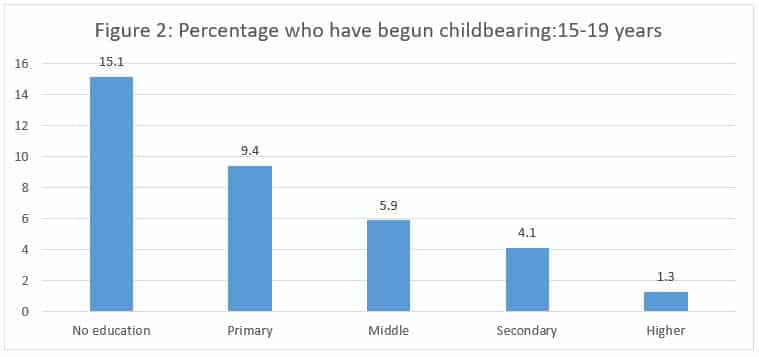

In Pakistan, eight percent of teenage women between 15-19 have begun child bearing and it has remained unchanged since 2012-13, NIPS, (2018). Young women, aged 15-19, with no formal education are at a higher risk of teenage childbearing. Around 15 percent of the teenage ever-married girls with no formal education had already begun childbearing.

Source: PDHS 2017-18.

Disconnect between Knowledge and Use of Contraception among

Married Women Aged 15-19

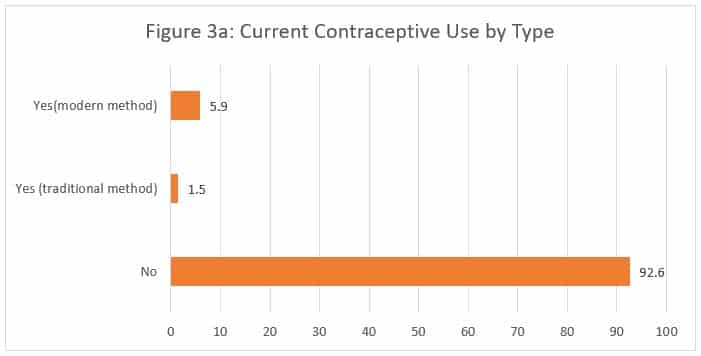

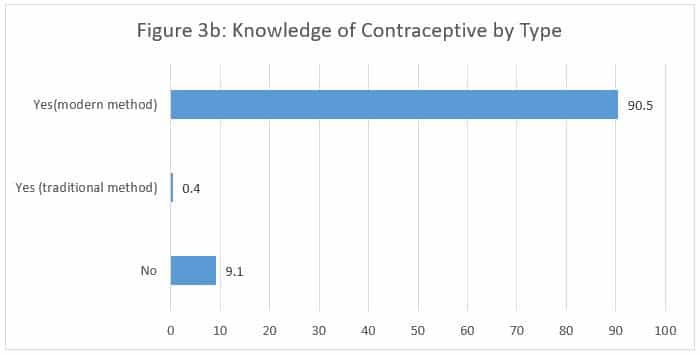

Around 93 percent of currently married teenage women (15-19 years) are not using any contraceptive methods. However, when it comes to knowledge about contraceptive use, only 9 percent of the teenage women did not know any family planning method. A vast majority of women (90.5 percent) know about modern contraceptive methods (Figure 3a & 3b).

Unintended Fertility and Unmet Need for Family Planning among Young Women

Despite the universal knowledge of family planning methods, particularly modern methods, the lack of use of contraception results in unintended fertility. According to PDHS 2017-18, around 4 percent of the births among mothers less than 20 years old are mistimed. Unmet need for family planning is higher among women aged 15-19. Nearly 18 percent of the young currently married women have an unmet need for family planning in Pakistan, NIPS, (2018).

What Can Policy Makers Do?

Experiential evidence abounds on the benefits of family planning programs. In most developing countries, family planning programs have proven to be cost-effective and high-impact. They have been shown to invariably improve maternal, neonatal, and child health outcomes. Our policy makers need to recognise the importance of investing in the family planning needs of young couples as almost half of Pakistan’s population is below age 20. Investment on the youth will potentially bring about socio-economic development within a short time frame.

(1) Support Youth’s Access to Contraception

Our public health system does not recognise young unmarried men and women as key targets of family planning programs so they remain underserved by sexual and reproductive health information and services. Most youngsters enter adolescence with little to no information and without any preparation of puberty. Much of the learning comes from peers and social media. Similarly, young couples start their family life without any proper planning. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that couples generally begin childbearing immediately after marriage and contraceptives are scarcely used before the first birth in Pakistan, NIPS, (2019).

Counselling of young married couples before marriage, therefore, is imperative and hence, reproductive health and family planning strategy must focus on younger men and women and adolescent boys and girls. Given the large youth cohort entering the reproductive life span, policies that assist in preventing, spacing, or delaying pregnancies should be encouraged. Counselling services, facilitation centres, follow up mechanisms, and easy and affordable access to contraceptive methods encourage young couples to use contraceptives, Streifel, (2021).

(2) Ensure Youth-friendly Services for Family Planning.

Counselling services and distribution of contraceptives are the responsibility of family planning units. However, access to these services is different or somewhat limited for unmarried youth, which may be caused by the service providers’ reluctance and culturally induced inhibition in discussing sexuality with the young unmarried boys and girls, and their lack of training.

Similarly, the inadequate number of community health workers needs urgent attention of the policy makers. Another often overlooked missing link is the very scant involvement of young males in family planning activities. Any family program has to have the involvement of males of the family in order for it to be fully successful. In addition, lack of transportation, financial constraints, and confidentiality are other barriers/concerns which need to be addressed.

Research has shown that providing youth-friendly services significantly reduced teen pregnancy, Brindis, et al. (2005). Therefore, to reduce unintended fertility, family planning services and facilities must be made accessible to both young married and unmarried people.

(3) Revision of Legal Age of Marriage

Pakistan has committed to end underage marriages by 2030 under the UN’s SDGs. Pakistan’s legal age of marriage, set at 16 for girls and 18 for boys, besides being discriminatory in gender terms except in the province of Sindh where it is 18. The age at marriage is the main determinant of the number of children each woman will have (Bongaarts, 1982).

Underage marriage has serious consequences for both the mother and child’s health. Besides, women who marry before the age of 18 drop out of school more often and are less likely to work. They are at higher risk of physical and sexual violence. In order to protect young girls’ rights to health and education, and to prevent underage pregnancies, government must immediately revise the legal age of marriage upwards without waiting till 2030.

(4) Collaborate with Community and Traditional Leaders to Address

Sociocultural Barriers

Kinship structures and community norms drive human behaviour. These traditional institutions are ensconced within and inside an outer circle of national socio-political institutions, ideologies and power dynamics, Kanein, et al. (2016). Gender norms of the society make certain behaviours of men and women socially acceptable. That in turn impacts the sexual and reproductive health of a woman. These gender norms make sexual ignorance for women acceptable and even desirable, and give sexual power to men thereby making men decide matters of reproductive health including contraceptive usage.

This very gender discrimination is the driver behind child marriage. Lack of education and child marriage contribute to lower empowerment for women, Lee-Rife, (2010). This is how patriarchal gender system becomes part of a society’s value system and is perpetuated. As Stith (2015) pointed out “Patriarchal religious traditions celebrate girls as young wives and mothers, not as the girls they are. This appropriation is a key component of patriarchal power and girls’ disempowerment.”

The shackle of patriarchal power can be broken only by interventions designed to break the socio-cultural barriers that come in the way of family planning. That entails sensitising the community elders and traditional leaders, including religious clerics, on the benefits of gender equality and involving them in public debate and policy formulation and implementation process about underage marriage. This would help in prevention of the continuing cycle of reproduction of discriminatory norms and may ultimately lead to the legislation required for raising the legal age of marriage.

(5) Creation of Demand for Family Planning

Pakistan’s family planning program is mostly focused on the supply side of contraceptives. However, recent PDHS 2017-18 shows a percentage decline in contraceptive use which may signify lack of demand. Therefore, instead of solely focusing on the supply side, the creation of demand for family planning and for contraceptives is necessary. This can be achieved by focusing on socio-economic development particularly on the women education as well as economic participation. This will, in turn, increase the opportunity for having children even for young couples

REFERENCES

Brindis, C. D., Geierstanger, S. P., Wilcox, N., McCarter V., & Hubbard, A. (2005). Evaluation of a peer provider reproductive health service model for adolescents. Perspective on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37(2), 85–91.

Bongaarts, J. (1982). The fertility-inhibiting effects of the intermediate fertility variables. Studies in Family Planning, 13(6/7), 179–89.

Jennifer, S. (2015). Child brides to the patriarchy: Unveiling the appropriation of the missing girl child. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 31 (1), 83–102.

Kane, S., Kok, M., & Rial, M. et al. (2016). Social norms and family planning decisions in South Sudan. BMC Public Health 16, 1183.

Lee-Rife, S. M. (2010). Women’s empowerment and reproductive experiences over the lifecourse. Social Science Medicine, 71(3), 634–42.

National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and Macro International Inc. (2018). Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Islamabad.

Streifel, C. (2021). Policy brief: Best practices for sustaining youth contraceptive use. Population Reference Bureau.

Saima Bashir