Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Disappeared But Never Forgotten

General Iberico Saint-Jean, the governor of Buenos Aires at the time of the junta, is quoted as saying: “first we will kill the subversives; then we will kill their collabourators; then… their sympathisers; then… those who remain indifferent; and finally we will kill the timid.” Pakistan’s military establishment, it would appear, had also thought along the same lines. So first, it killed those in the ‘peripheries’ who resisted injustices; then it killed those in the major cities who amplified tales of horror from the ‘peripheries’; and now finally, it has decided to kill even those who did not speak till the acts of tyranny reached their homes.

Understanding the origin of enforced disappearances is essential to understanding the nature of the State of Pakistan. For this purpose, we must go back in time to 7 December 1941, when Adolf Hitler issued the Nacht und Nebel Erlass (Night and Fog Decree), the purpose of which was to forcibly disappear persons in Nazi Occupied Territories who were deemed to be a threat to German security. It is estimated that around 7000 people were subjected to these enforced disappearances and likely executions.

This practice has subsequently been used in various parts of the globe from Argentina to the Philippines. Between 1973 and 1990, it is estimated that over 3,000 people had been forcibly disappeared and/or extra judicially executed in Chile during the brutal military regime. Similarly, in 1984, Argentina’s Comision Nacional sobre la Desaparicion de Personas (CONADEP) reported 8961 deaths and disappearances in the period from 1976 to 1977 – again, under brutal military rule. For context, Pakistan’s Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED) reported 9294 cases as per its Monthly Progress Report dated 1 February 2023.

The key difference between places like Argentina and Chile, on the one hand, and Pakistan, on the other is the refusal (by the latter) to take any steps to end impunity. While the problem is far from resolved in Chile, there have been around 1134 trials that have led to at least 2500 convictions of those involved in the heinous crime. In Argentina, several former soldiers have been tried and convicted for their involvement in the ‘dirty war’. In Pakistan, however, till date, not a single perpetrator behind enforced disappearances has been tried, let alone convicted or held accountable in any way for involvement in the practice.

Perhaps part of the reason for the unending culture of impunity in Pakistan is the complicity of all – the executive, the constitutional courts, law enforcement and intelligence agencies – in the practice. As a result of this complicity in the practice at every level, the families of the disappeared are left entirely at the mercy of their loved ones’ abductors. This cruel and complex nature of enforced disappearances has been termed by the Islamabad High Court (in paragraph 20 of the Mahera Sajid Judgment) “an unimaginable paradox when the State and its functionaries assume the role of abductors.”

Interestingly, in Argentina, amnesty laws were introduced that bolstered this culture of impunity, however, this was brought to an end by the Inter American Court of Human Rights in 1992 – to a large extent – in its Judgment which held that such amnesties are in contravention of the State’s obligation to ensure access to justice for victims. In Pakistan, this right to seek justice is often denied by the Constitutional Courts themselves.

Such is the case of Feroz Baloch, a Baloch student who was disappeared while on his way to the library at Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi on 11 May 2022. Feroz’s cousin, Rahim Dad, filed a habeas corpus petition before the Lahore High Court Rawalpindi Bench, which was dismissed vide order dated 9 June 2022, on the ground that “the matter is being heard” by the COIED.

On the COIED, the Islamabad High Court, in order dated 25 May 2022 passed in Mudassar Naaru and other connected missing persons cases, has already observed that the “Commission, rather than achieving its object, has become a forum which contributes towards making the agony and pain of the victims more profound.” The Islamabad High Court has found that the COIED’s “proceedings seem to have become a mere formality and its adversarial nature undermines and violates the dignity of the loved ones. Its role is no more than a bureaucratic post office.” Yet, several Constitutional Courts would rather see families suffer in the COIED rather than exercise power vested in them to enforce fundamental rights by disbanding this sham Commission, which in fact fuels the culture of impunity.

So effectively, families of the disappeared are denied their right to have their legitimate grievances redressed. These families – the ones who are able to make it to the Constitutional Courts – are still better off than most. Most family members wait for months on end for registration of a First Information Report. Thousands of others appear before the COIED, hearing after hearing, only to partake in proceedings that are a mere eyewash.

“When I went to the Commission, I was told I was doing a ‘drama’ and that my son had gone somewhere voluntarily.” These are the words of Buss Khatoon, the mother of disappeared Baloch activist, Rashid Hussain, whose fate and whereabouts remain unknown till date. Rashid was detained by the United Arab Emirati Security Forces on the E88 Highway while travelling from Sharjah to Dubai City on 26 December 2018. As per the Certificate for Entry or Exit (Last Travel), issued by the UAE’s Federal Authority for Identity and Citizenship, Rashid exited Al Bateen Airport for Naushki on 22 June 2019. No carrier or flight details are mentioned on the Certificate, which indicates that Rashid was likely brought back to Pakistan via Government or military aircraft, or special chartered flight.

After several years, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally admitted before the Islamabad High Court, on 16 February 2023, that Rashid was extradited to Pakistan. No Government functionary is willing or able to disclose to the Court where Rashid is being detained at present, or what condition he is in. After each hearing, I have to explain to the family members why, despite this admission, no action has been taken by the Constitutional Courts to protect Rashid and his family’s fundamental rights.

Such is the story and suffering of Rahat ul Nissa, the mother of disappeared journalist, Mudassar Naaru, who was abducted on 20 August 2018 while on vacation in Kaghan with his wife, Sadaf, and then six-month old son, Sachal. Sadaf ran from the COIED to the courts to the press clubs but the toll of this unending agony was more than she could bear. She passed away in May 2021, leaving behind Sachal, who is also now, like his mother, running from courts to press clubs with his dado.

There are also horror stories of several family members disappeared from one home, one after the other. One such heartbreaking story is that of Sultan Mehmood’s two brothers – Zahid Ameen and Sadiq Ameen. Zahid was disappeared on 7 November 2014 and despite issuance of his production order to the Inter Services Intelligence in 2021, the same has not been complied with. Sadiq, who was pursuing Zahid’s case before the Commission and the Constitutional Courts, was then subjected to an enforced disappearance on 10 March 2021. Their father – an elderly man who fought till his last breath for his sons’ recovery – passed away in August 2022 without being able to say goodbye to his sons.

When Zahid and Sadiq’s family members approached the Constitutional Court, as has now become a routine (but absurd) practice there when approached in writ jurisdiction, the Lahore High Court (Rawalpindi Bench) cited the proceedings in the COIED as a basis to close the case before it. And so we go around in circles: no one has the forcibly disappeared and the State cannot seem to find them but anyone even mistakenly in the vicinity of General Headquarters on 9 May, can be tracked, traced and arrested within hours.

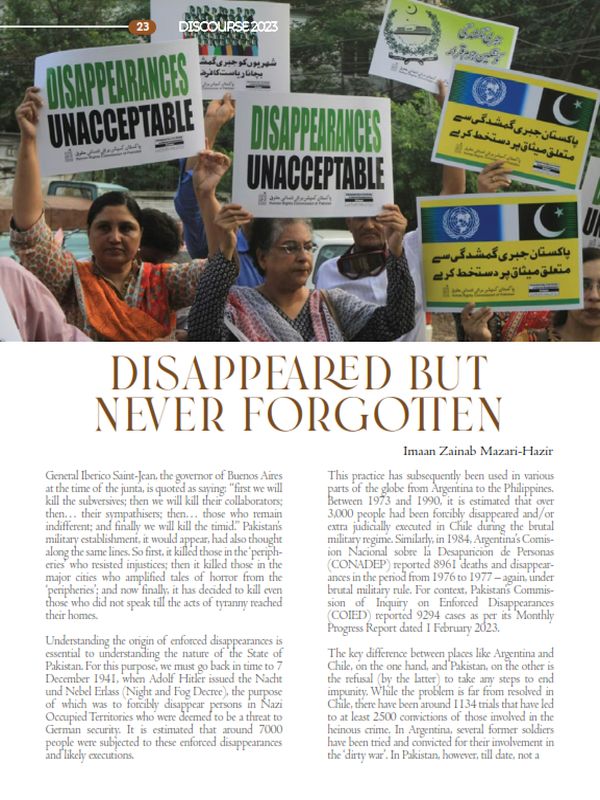

While the Commission and the Courts may continue with their apathetic approach towards families of the disappeared, the growing resistance to the heinous practice within civil society renews hope in the power of the people. The callousness of the State has brought together oppressed communities to struggle together against the phenomenon of enforced disappearances.

One recent illustration of that solidarity, which serves as a source of great inspiration, is the visit by leaders of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement to the Voice for Baloch Missing Persons sit-in camp, which has been ongoing for over 5000 days. Against every act of ruthless oppression, the most vulnerable continue to resist peacefully. And so we reiterate our commitment that though thousands may be forcibly disappeared, they will never be forgotten. As disappeared engineer, Sajid Mehmood’s daughter, Aymun Sajid, eloquently puts it: both the disappeared and the families of the disappeared are “refusing to disappear.”

The author is a lawyer, human rights activist and international law researcher. She is a founding partner of MH Advocates & Legal Consultants and can be found on Twitter as @ImaanZHazir.