Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

The Haves & The Have-Nots: Pakistan’s Climatic Catastrophe

When George Orwell wrote: “if you want a vision of the future imagine a boot stamping on a human face: forever” – he wouldn’t have known, but was perhaps narrating the bitter truth embedded in the future human security threats and the gruesome inequity engulfing them. A contemporary day example of this is Pakistan and other nations of the Global South, which are experiencing a climate-destabilised future. The adverse impacts of climate change are right here, with Pakistan at the epicentre of it.

- Pakistan’s Growing Climatic Calamity

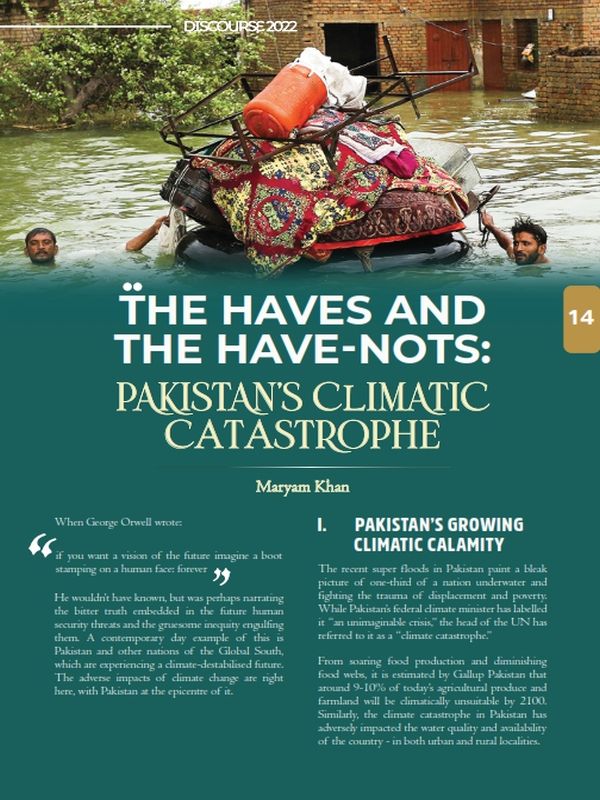

The recent super floods in Pakistan paint a bleak picture of one-third of a nation underwater and fighting the trauma of displacement and poverty. While Pakistan’s federal climate minister has labelled it “an unimaginable crisis,” the head of the UN has referred to it as a “climate catastrophe.”

From soaring food production and diminishing food webs, it is estimated by Gallup Pakistan that around 9-10% of today’s agricultural produce and farmland will be climatically unsuitable by 2100. Similarly, the climate catastrophe in Pakistan has adversely impacted the water quality and availability of the country – in both urban and rural localities. The World Bank’s 2021 report stipulated that the average mortality in Pakistan due to water-borne issues is 9 times higher in comparison to European nations. Even more worrying has been the severe risk faced by coastal cities such as Karachi, which too is not free from climate havoc. The recent urban flooding in Karachi highlights how flood-related mishaps have spread like wildfire throughout all areas of the city – whether more or less developed.

However, the question in focus is why does Pakistan bear the gloomy brunt of climate change when it remotely cannot be qualified as a global carbon emitter? The answer is Branko Milanovic’s “The haves and the have-nots – an idiosyncratic history of Global inequality.”

- The Global North & Global South Debates – Expanding on the Have & Have nots

Simply to be understood, the haves and have-nots is a global north versus global south debate. The bridge between the rich carbon-emitter hegemonic powers and the vulnerable, developing world has been ever increasing, and what has exacerbated this situation further of have and have nots are the recent super floods in Pakistan. Walls collapsed, homes broken and nothing left intact – the recent floods in Pakistan are a climatic catastrophe, leaving almost 1400 dead and 33 million displaced.

Analysts have been unanimous that the alteration in the recent torrential rains in Pakistan was climate-change induced – i.e. they were rain-induced and not the usual riverine floods. The norm in Pakistan’s monsoon season has been that the current starts from the Bay of Bengal, enters India and travelling from northern Pakistan to southern Pakistan. However, this year monsoon rains entered the Southern parts of the country, wreaking havoc eventually in the Northern section of the country.

Like all other international security issues circumambulating the 21st century, climate change pits the interests of wealthy countries against those of the developing world. Statistically analysing, the US has produced 25% of all carbon emissions since the 18th century, whilst up until 1950 Europe produced more than half of the world’s carbon emissions. Yet, against these statistics, it is the countries of the Global north living at the expense of the Global south. The global North, therefore, needs to own up to its role in the havoc and the disaster it’s causing.

For instance, Europe’s novel welfare system, which is a glaringly perfect image of what a serviceable and well-governed continent should be like, is derived from the wealth it accumulated during colonial times. However, the rich countries have been persistently denying their responsibilities which are beset in history – whether it is colonialism, racial capitalism or the contemporary world’s ailing climate change, they are living at the expense of the global south. So, now when countries of the Global south demand compensation they are basically asking Global North to pay its debt.

Similarly in Pakistan’s case, the reparations that we as a nation demand from International forums and communities, unlike humanitarian aid, are not a form of charity but a reflection of what is inherently owed by rich carbon-emitting countries and firms to Pakistan – the one paying the price of their doings. Despite prior discussion in last year’s COP26 on the “Loss and damage funding” – the issue and the debate remained in question and indefinitely unsettled.

Therefore, the need of the hour to avert future climatic calamities, and for Global North to dramatically reduce its carbon footprint. One key point to be noted is that the principles of justice and collective responsibility are ever so important for countries like China and the United States considering their shared monetary and fiscal agreements with Pakistan. Climate change is as compelling a shared existential crisis for all these countries because the truth is that the issue is integrated with the global system and has downstream effects on everyone.

The question then is who should pay for Pakistan’s loss and damage? And what should be the future preventive measures to prevent the disproportionate climatic brunt borne by the global south countries?

- Future Roadmap: A call for Climate justice?

The answer lies in the 3-legged climate strategy of — mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage. Mitigation aims to diminish the greenhouse effect by curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation seeks the execution of proactive measures to protect climate-change communities. Loss and damage aim to help climate change victims after they have experienced climate-ridden destruction.

However, this three-legged climate action strategy has been shaky in dealing with climate change at all levels. There is a rampant need for restructuring and re-evaluation of this strategy to avert the climate crisis. To meet the Paris Climate agreement’s most ambitious goal of keeping global temperatures below 1.5-degree celsius, the mitigation plan needs to be amplified enormously. According to a 2020 climate report, the overall global emissions must fall by approximately 8% by the end of this decade to avoid a larger climate calamity.

Second, climate adaptation measures have also been rendered futile. Strategies like the Green Climate fund or the Adaptation fund to ensure climate adaptation have also become all talk, and no walk. From promising $100 billion per year for climate adaptation to COP26’s Glasgow climate pact – all deals have failed to fall through.

Thus, as mitigation and adaptation endeavours fail – the only viable solution left to the ongoing climate crisis is the operational third leg: the loss and damage. Analysts define “loss” as irremediable loss of human lives, biodiversity and indigenous cultures. While “Damage” encompasses the negative climatic implications but where repair is still possible. For Pakistan’s case too, the answer is simple. The current waves of climatic floods in Pakistan have provided the global polity with a chance to revisit the loss and damage strategy. To begin with, even though time sensitive, we should take the opportunity of embedding loss and damage strategy as an official game plan submitted as a formal draft to the UNFCCC secretariat before COP27 in November. This will catalyse international support and solidarity for Pakistan.

As climate leaders prepare for COP27 in Egypt in November of this year, the heart-wrenching images of Pakistan’s massive climatic suffering will be glaringly prominent in everyone’s mind. The humanitarian and climatic tragedy occurring in Pakistan is a shrewd excerpt which should be brought forth under serious consideration for a loss and damage mechanism – an indefinite reminder that ad-hoc commitments are not sufficient, but what is needed is an actual effort from Global North.

The author is a graduate in Economics & Politics from LSE & the founder of climateactionpakistan