Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Justice: Not a Fundamental Right but a Neoclassical Economic Commodity?

Justice: Not a Fundamental Right but a Neoclassical Economic Commodity?

Saddam Hussein, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

Anwar Shah, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.

INTRODUCTION

A society is composed of agents who are dependent on one another for their routine chores. The human species is unique, as it gauges actions among themselves based on morality and ethics. Hence, there exists a propensity for any individual to counter a dispute with another in society. Therefore, every individual in the society has the right to access to justice so that he or she can resolve disputes and get rid of the uncertainty factor for future transactions. For this reason, access to justice has been the corner stone of fundamental human rights in all the developed societies across the world.

The Constitution of Pakistan is no different from others in that it indemnifies access to justice to all its residents without any discrimination of any kind. Two articles are worthy of special mention in this regard: – Article 4 and Article 10-A of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan offer unequivocal details on the subject of how to ensure the provision of justice to citizens. Keeping in view the above-mentioned articles, it can be deduced that justice must be inexpensive and swift for every citizen of Pakistan.

Unfortunately, the institutional mechanisms and the organisational configuration of Pakistan’s judicial system is such that it necessitates several formalities disguised as the proper procedures or codes of conduct for getting justice. The litigants have to pay for different costs which include lawyers’ fee, court fees, and cost of documentation etc. Therefore, it can be inferred that access to justice and the institutional framework for obtaining justice in Pakistan is not according to what is enshrined in the Constitution.

JUSTICE AS AN ECONOMIC COMMODITY

This notion of justice as an economic commodity is in line with the neo-classical school of thought in economics. In context of the framework, justice is similar to an economic commodity, it has all the features of a commodity, and an individual has to purchase it as one. This would mean that justice is responsive to factors such as supply and demand, and price plays the key role in the whole framework. Now in a market situation, willingness to pay is reflected through demand and willingness to accept is translated into supply. If there is perfect competition in a market, then the price mechanism will be at its best.

In a perfectly competitive market, those willing to pay a higher price will crowd out those willing to pay a lower price. Similarly, in the supply side, having low willingness to accept will exclude those having high willingness to accept. This whole mechanism generates an equilibrium position between the consumer, who is willing to pay a higher price, and the supplier having a low willingness to accept. So, the outcome is considered to be optimal – a situation in where goods flow towards those who require it the most, and are also willing to pay a competitive price for it. Resultantly, the supplier’s surplus is relished by those who were willing to pay a higher price, but actually pay a bit lower, and that willingness to accept was low, but actually get more than that.

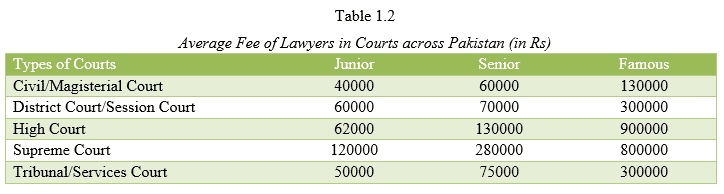

The market for justice operates on the same pattern, having two sides of a conventional market structure i.e. a demand side – litigants who are pursuing justice and are ready to pay a price for it, and the supply side – lawyers who are eager to assist in provision of justice, but with some particular price. Consequently, an equilibrium price is reached with an outcome such that only those who can afford and are willing to pay the specific price have access to. Those who cannot pay the price are barred from access to justice. The point to note here is that all this holds true if perfect competition exists in the justice market.

INFORMATION ASYMMETRY AND TOURIST MODEL

Whereas, in justice market no perfect competition exists as there is information asymmetry in terms of due process of justice at the consumer end. By using this dysfunctionality to their advantage, lawyers enjoy a monopoly in the justice market. The justice market can also operate like a tourist model market, where those seeking justice visit one lawyer, and then there seem to be no incentive for them to seek another lawyer, because there is information asymmetry, as it will add to the transaction cost. This setting puts lawyers at an advantageous, with bargaining, asking for much higher price creating more exclusion. Thus, an equilibrium point is attained at where only those people can have access to justice who can afford to pay a higher price. All others are unable to arrange for the (higher) equilibrium price are barred from having access to justice.

In Pakistan, the inclusion of lawyers in the process of justice without proper checks and balances is itself an impediment in the way of demand side’s accessibility to justice. If we look at the whole picture, there are generally two parties that demand justice whenever and wherever a dispute arises. Hence, technically they require a third party to facilitate in solving their dispute without being party to it. Thus, in principle the third party which happens to be lawyers in the case of Pakistan, should not have any kind of monetary incentives attached to the case they are handling. Nonetheless, attaching monetary benefits with the case proceedings is a big hurdle in access to justice, because the longer the case continues, the greater its monetary value to the lawyers. In more serious cases, the demand for justice would be more inelastic and lawyers would have an advantage asking much higher fee. The compulsions or constraints of the common man make the justice market more favourable for the lawyers, eventually making justice accessibility costly.

TRANSACTION COST OF LITIGATION

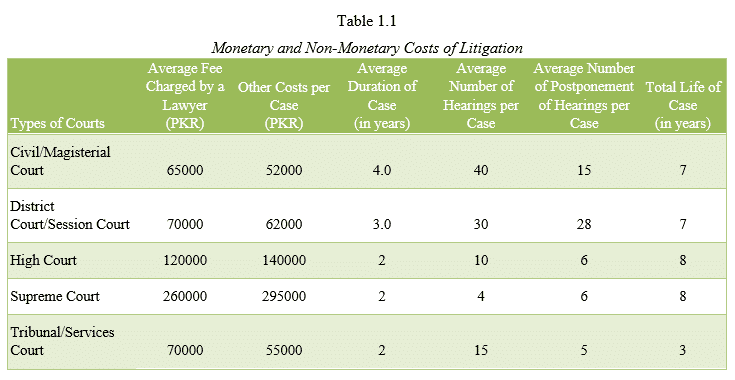

The findings of the study”, offers an outline of the different sorts of costs related to different level of courts in Islamabad. Table 1.1 shows the monetary and non-monetary cost per case in a court. It is obvious from the Table 1.1 that a litigant would have to wait for almost four years on average while settling a case in a Civil or Magisterial court. Additionally, the litigant may have to appear 40 times on average before the court for hearings in the four-year period. A point worth mentioning here is that out of 40 times, on average 15 times the litigants face rescheduling of a hearing. It does not end there: after waiting for almost four years, the litigants may have to wait extra three years on average for the thorough disposition of the case. In all this, the litigants have to bear the cost of legal fees of almost Rs 65,000. When other costs are added, which could include cost of conveyance, accommodation and meals, then the price of justice gets is much greater than envisaged.

_____________________

“The study is based on a very brief random digital survey from the sample of 260 respondents. These include 130 legal experts 130 from clients from across Pakistan. We tried to ascertain the sample according to Census 2017. So, out of 130 in each category, we chose 64 respondents from Punjab, 27 from Sindh, 22 from Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, 07 from Baluchistan and 05 each from Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

Note: All the figures are slightly rounded in this document for simplicity and better understanding.

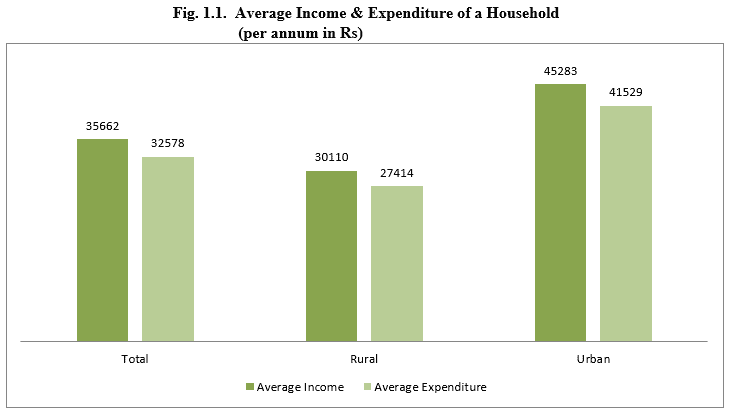

The affordability of accessing justice for a Pakistani citizen is calculated from their average income. For this, the latest data available from Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES 2018-19) is use. Figure 1.1 shows the monthly average income and the expenses of the average Pakistani household.

From the data available, it can be deduced that overall monthly average income of a household is about Rs 41,545. Similarly, the monthly average income of a rural household is around Rs 34,520, while the monthly average income of urban household is approximately Rs 53,010. The monthly average expenditure of a Pakistani household is about Rs 37,159, whereas for a rural household, the average monthly expenses are Rs 30,908. The average monthly expenses for an urban household is Rs 47,362.

Based on the given data, the average income of a Pakistani household per annum is approximately Rs 498,540. The average earnings of a household in rural and urban areas of Pakistan is Rs 414,240 and Rs 636,120, respectively, whereas the average expenses are around Rs 445,908 per annum for a common Pakistani citizen. Likewise, for a rural and urban household, the average expenses per annum are Rs 370,896 and Rs 568,344, respectively. So, on average a common Pakistani’s expenditure accounts for around 90 percent of household income.

Therefore, the savings of a household per annum make up around Rs 52,000. If faced with a legal matter in the Civil Court, the household will be unable to pay its legal fees, which could amount to Rs 65,000, not to mention other costs that are incurred during the total life of the case. The fees of higher courts are more than that of the Civil Courts, so they are out of the reach of a common citizen.

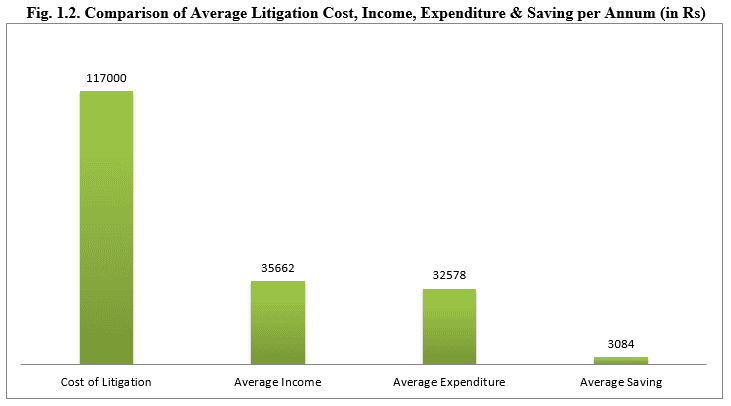

So if we compare cost, income, expenditure and savings, the picture is quite gloomy. If we take the average cost of the lowest court, it amounts to Rs 11,7000. Whereas, the average income and expenditure per annum are Rs 35,662 and Rs 32,578. This means that on average the savings of a common Pakistani is Rs 3084 per annum. If we compare the cost and savings, access to justice is beyond the means. The government by law provides a prosecutor in such cases but implementation is in a shambles; in parallel there is no string incentive for the lawyer to take deep interest in the case. This jeopardise the whole proceedings of the course.

Hence, it can be said that accessibility to justice is very challenging, if not unmanageable, in civil courts for a common Pakistani citizen. This indicates that on average, an ordinary Pakistani citizen has either to borrow or sell some of their possessions for contesting a case in civil courts. It is noteworthy to mention that calculations are centreed on the supposition that a household faces one legal matter once in the whole year. Therefore, the estimation about exclusion will become worse by relaxing the supposition.

THE SLUGGISHNESS IN THE JUSTICE MACHINERY

The delay in court proceedings is another dilemma which indirectly favours the financially strong. It takes years to reach a conclusion, that too with lacunas. The prolonging of cases usually favours the elite, as the poor are compelled to give up the case against financially strong party because they can no longer afford the lawyer’s fee and other costs and give up cases with unconditional apologies or reach a settlement outside the court, which is often against their wishes.

The delay in the dispensation of justice has reached a point where it has become a factor of injustice. The volume of backlogs, the loopholes and complexity in procedural law, and the case management system are some factors which delay and deny access to justice for many. The court machinery is overloaded, slow and not readily accessible to all.

The delay in civil cases can be addressed from two standpoints: one unintentional and the other intentional. Unintentional delay occurs out of our age old legal system, while the intentional one must be penalised with effective implementation. That is why, the justice delivery system in Pakistan is time consuming. The existing regime of civil suits in Pakistan is governed by the Code of Civil Procedure enacted in 1908 – with no solid attempt to amend the rules of procedures according to fit in with contemporary times. The causes of backlogs and delays to the disposal of cases are systematic and profound. The legal system’s failure to impose the necessary discipline at different stages of trial of cases allows dilatory practice to protect the case life. Therefore, the life of the cases extends to over few years at least.

It has also been observed that much of the delay occurs as the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure are not properly observed, leaving speedy disposal of cases compromised. After filing a complaint, the process fee is usually not paid for a period of time; therefore, the summons to the defendant is also not served in time. After the defendant files his appearance, his advocate often seeks long adjournments to file written statements. After the pleadings are closed, there comes the stage of producing documentary evidence before issues are settled, but usually no documentary evidence at this stage. Little use is made of the provisions for discovery and inspection of documents and for serving interrogatories.

If these provisions were properly used, the controversy between the parties can often be narrowed before the cases go for trial. However, what usually happens is that when the suit comes for trial, the advocates sit down in the court, open their file, probably for the first time, and begin labouriously to prepare lists of documents. Countless hours are wasted in this way.

Also, Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 binds the defendant to submit a written statement within a stipulated period. In most cases, the defendant intentionally does not comply with the time-limit provision for filing such a statement. Due to this lapse application are filed at this stage before filing written statement, causing unnecessary delays in the disposal of proceedings. Where the defendant has no defense, he/she is naturally interested in prolonging the trial with a view to put off the evil day as long as possible.

Another of the reasons for delay in the disposal of suits is the readiness to grant adjournment either to r the court’s own advantage or for the convenience of the parties. The liberal attitude of the court in respect of adjournment is one of the main causes for the inordinate delay as every such adjournment causes months of delays. Moreover, the judges’ hands are tied as to what is produced in black and white; they cannot see or decide beyond that, added the judges.

There is an urgent need of comprehensive reforms for better and effective justice delivery. The way forward is to implement a robust incentive mechanism with strong checks and balances to address all of the above issues.

NON-MONETARY COSTS OF LITIGATION

If we analyse the other costs which fall under the category of transaction costs, we would come to a conclusion that upper middle income and higher income classes in general could manage with other costs in such a way that these costs would not affect their routines lives. There would be a slight impact if it does. The only costs which could be associated with the higher income classes class seem to be with regard to their reputation and mental stress. Owing their high incomes this group hires lawyers or teams of lawyers who handle their legal affairs very effectively.

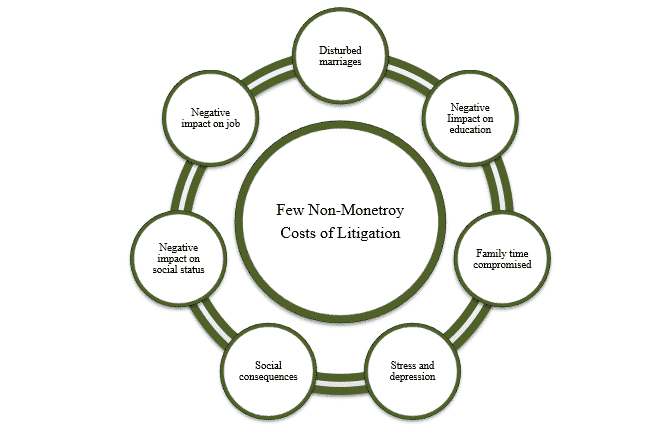

The poorer segment of the society, including the middle classes, are not in such a position. They have to do trade-offs in their budget allocations. They might have to spend less on food to leave money for lawyer fee, or may take loan, causing mental stress and social problems. Thus, other transaction costs associated with seeking justice in Pakistan implicitly favours and consolidates the advantageous position higher income class. Then there are some no-monetary costs as well for the litigants, as shown in the diagram below.

Inn this type of setting, a common citizen is constrained to opt for extra-legal justice system, also known as the informal system. The advantage of the informal system is that although it can provide a speedy dispensation of a case with minimum transaction costs, it does not offer any strong support for common citizens. With the exception of few areas and urban centres, most of Pakistan is, in one form or another, based on the structure of feudalism, with the feudal elites and other influential dispensing justice. With the power and patronage system as a backdrop, these influential, almost always men, often favour the people close to them. Moreover, one cannot appeal against the decision and often with the guilty (including their families, against all basic human right principles, become socially pariahs.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it would not be incorrect to see the common people of Pakistan as acquitted sufferers of a malevolent judicial system, run largely for the advantage of the elite. With few exceptions where judiciary had taken a pro-active role and made courageous decisions upholding rule of law, the elite have most often been successful in co-opting the judiciary and would make them decide major cases in their favour. On occasions when judges have upheld the rule of law, the decrees could not be implemented on the ground because whole of the state machinery would be behind the powerful.

It would also not be wrong to say that the justice system in Pakistan is an extension of a dominant coalition conducting politics by other means when and where needed. Moreover, the state of justice system is not only politically responsive, but it is employed frequently as an effective weapon. A large number of fake cases are brought purposefully by politicians for the character assassination, damaging the reputation of rivals and also as a bargaining tool in striking deals with their adversaries.

The way out of this legal morass is to put timelines for civil cases and heavily penalise those who fail to comply. Rules of procedures should be amended with forensics should be at the core of proceedings. Besides state sponsored prosecutors, more financing models and mechanisms, such as legal-aid, should be introduced for those who cannot afford large legal bills. There should be checks and balances on lawyers and judges as well. Third party monitoring and evaluation should also be considered.

Last but not the least, if the justice system acts as a neo-classical market, then state at least should regulate it.

REFERENCES

Agmon, S. (2021). Undercutting justice—Why legal representation should not be allocated by the market. Politics, Philosophy & Economics.

Cadigan, M., & Smith, T. (2021). Are you able-bodied? Embodying accountability in the modern criminal justice system. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice.

Dolderer, J., Felber, C., & Teitscheid, P. (2021). From neoclassical economics to common good economics. Sustainability.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, V., Grajzl, P., Sustersic, J. and Zajc, K., (2012). Judicial incentives and performance at lower courts: Evidence from Slovenian judge-level data. Review of Law and Economics.

Epstein, L., (2013). The Economics of judicial behaviour. Edward Elgar.

Nekokara, M. A. (2016). Access to justice and legal aid. Dawn News. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1301948.

Pleasence, P., Balmer, N. J., & Hagell, A. (2015). Health inequality and access to justice: Young people, mental health and legal issues. London, England: Youth Access.

Shah, A. (2007). Can we expect Inclusiveness within the Institutional Framework of Exclusiveness? An empirical analysis of the court cases in Islamabad. Higher Education Commission, Islamabad.

World Justice Project. (2020). The rule of law in Pakistan. Washington, DC.

Yuchuan, L. I. N. (2021). Stability of Justice and Market Socialism: Centreing on A theory of Justice. Journal of Renmin University of China.