Pakistan Institute of Development Economics

- Home

Our Portals

MenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu - ResearchMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenuMenu

- Discourse

- The PDR

- Our Researchers

- Academics

- Degree Verification

- Thesis Portal

- Our Portals

Policy Insights to Maritime Economy in Pakistan

Policy Insights to Maritime Economy in Pakistan

The term “Blue Economy” originated in 2012 from the Rio+20 Conference of the United Nations on Sustainable Development and Growth.[1] Given the vastness of oceanic resources, the blue economy has been touted as the panacea for all economic woes of less developed coastal countries. It basically refers to leveraging the coastal and marine resources for economic benefits, emphasising sustainable economic growth and environmental conservation.

United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development directly linked sustainable economic growth and Blue Economy via SDG 14. World Bank defines Blue Economy as: “Sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem.” Due to its international obligations for SDGs, Pakistan has integrated SDGs into its domestic development agenda, which implies that Pakistan is cognizant of the blue potential.

INTRODUCTION

A Blue Economy that comprises marine or oceanic resources holds vast and untapped potential to drive economic growth in Pakistan. Investment in coastal and various categories of marine resources can help meet the food, transport, and energy needs of Pakistan. This is important in the context of slow economic growth, financial instability, volatility of investment, and ever-rising unemployment that Pakistan has experienced in recent years. It is time that Pakistan looks to coastal and marine resources to diversify its economy beyond traditional land-based investment avenues.

Pakistan has about 990 km long coastline, an Exclusive Economic Zone of 240 000 sq. km, and an additional continental shelf area of about 50,000 sq. km, making Pakistan an important coastal state. The exclusive geostrategic position of Pakistan lends its ports a unique significance concerning maritime trade. Furthermore, the construction of Gwadar as a transit and transhipment port under CPEC has further augmented Pakistan’s maritime potential as a key player in Indian Ocean Region.

Blue Economy of Pakistan offers a wide range of maritime sectors peculiar to the geostrategic and economic realities of the country. It includes conventional maritime industries, namely fisheries, coastal tourism, maritime transport, etc., and newly emerging areas of aquaculture and marine biotechnology, deep sea-bed mining, resource extraction, oceanic renewable energy, and maritime tourism. The construction and operationalisation of Gwadar Port have enhanced the scope of maritime transport in Pakistan. Noteworthy, maritime transport industries that offer great opportunities for investment in Pakistan are Port Development and Coastal Urbanisation, tourism, Shipbuilding, Ship-breaking/recycling, and Transhipment companies.

Pakistan is a lower-middle-income country,[2] with the economy growing at less than a 3 percent growth rate, whereas, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics suggests for Pakistan a potential of sustainable 8 percent growth annually. Being the 5th most populous economy globally with a population growth rate of nearly 2 percent, Pakistan might face precarious food security challenges in the future. The inadequacy of tax revenues and the balance of payment situation add to the economic woes of Pakistan. The extreme vulnerability to climate change needs new forms of decision making, such as investing more into blue economy because Pakistan might face food security problems related to the limited land and water resources (Rahman and Salman 2013). In a post-COVID-19 world, diversifying the economy beyond land-based avenues of investment remains difficult due to lack of capital but paradoxically remains a significant option to spur economic growth in Pakistan. Thus, Pakistan’s ocean and oceanic resources hold great potential to be leveraged, keeping up with the international practices of inclusive growth and community development.

Currently, the government is giving attention to the shipping sector up to some extent, after decades of neglect. After announcing the year 2020 to be the year of Blue Economy, the government did the right thing by amending the Merchant Marine Policy, 2001. The amended policy provides a range of incentives to private investors like reduction in gross tonnage tax, first berthing right to flag carriers, acceptance of freight charges in Pakistani rupees along with US dollars, Long Term Finance Facility, and other fiscal incentives. The provision of these incentives is highly laudable and will increase the size of the sector. Ministry of Maritime Affairs has sought a phased policy to transform and leverage the sector’s real potential. However, several measures are yet to be taken to improve the performance of the sector. Another significant factor is the competitiveness and capacity of the government bureaucracy to implement the policies. The lack of investment in training and infrastructure with lengthy processes makes the whole system slow and unattractive for investment despite these right policies.

___________________________

[1]In Rio+20, Member States decided to launch a process to develop a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will build upon the Millennium Development Goals. Hosted by Brazil in Rio de Janeiro from 13 to 22 June 2012.

[2]According to World Bank Classification, low-income economies are defined as those with a GNI per capita of $1,045 or less in 2020; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $1,046 and $4,095; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $4,096 and $12,695; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,696 or more.

INSIGHTS OF GOVERNANCE ISSUES

The Ministry of Maritime Affairs is Pakistan’s primary state institution overseeing all maritime sectors. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and the Merchant Marine Departments, as well as all three of Pakistan’s port agencies, namely Karachi Port Trust (KPT), Port Qasim Authority (PQA), and Gwadar Port Authority (GPA), are all under its umbrella. All three ports are not budgeted, meaning they earn and spend their budget on all concerned operations but require government approval through the Ministry of Maritime Affairs. The other stakeholders include Freight Forwarders, All Pakistan Shipping Association (APSA), Customs, Federal Board Revenue, and the banking sector. PNSC (Pakistan National Shipping Corporation) Regulations 1984, Marchant Marine policy 2001, and other department regulations culminate to make the national shipping policy.

Pakistan Merchant Marine Policy 2001 (MMP) was amended in 2019 and will continue up to 2030. According to amendments, no federal tax (Custom duty, income tax, and sales tax) shall be levied on Pakistan resident ship owning companies during the exemption period. All Pakistan flag vessels shall be given priority berthing at all Pakistani ports. PNSC is directed to continue to pay tax of US$ 1.00 per Gross Register Tonnage (GRT) on its shipping income annually. The new companies that accept Pakistani rupees instead of dollars for freight charges shall be incentivised for the first five years of shipping and pay a tax of US$ 0.75 per Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT).

As per United Nations Liner Code 1974, a country can lift 40 percent of its cargo in its own ships, which can even be raised to 60 percent without getting into the realm of unfair trading practices. Pakistan lifts only 10-11 percent of its international trade, thereby forgoing a substantial source of FE earnings. One of the changed clauses in the amended Maritime policy gives the first right of refusal to PNSC for hydrocarbons cargoes imported on FOB basis; this amendment is however contrary to the policy’s para 8, that gives cargo preference to Pakistani flag vessels over PNSC chartered vessels. Secondly, the MMP lacks the legal status that is enjoyed by an act or ordinance. Its provisions are subject to a decision made by the cabinet and Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) from time to time. Negligible amendments, extending MMP to 2030, and declaring the shipping industry as a strategic industry are not enough. Stakeholders consensus agree that previous policy did not yield fruitful results and extending it to further ten years may not work as well. Previously, incentives were withdrawn from time to time and reinstated, thus, rendering them inconsistent for long-term planning purposes (NIMA). The shipping sector is highly capital intensive and requires long-term planning for financing. Besides this, Merchant Shipping Ordinance 2001 (MSO) also needs to be amended and revised to create synergy between the basic commitment in the policy and legal instrument for its implementation.

It is the need of the hour to frame a comprehensive Marine Policy that must include each and every sector of the blue economy to ensure optimal use of ocean resources, rather than sticking to few ordinances and regulations. This will require all stakeholders’ input; the stakeholders having the responsibility of governance is of core importance to kick start blue economy development.

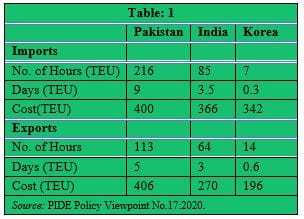

The need is to overcome the procedural inefficiencies as well as improvement in service delivery to leverage the actual potential. Pakistan has a high compliance cost as compared to other regional countries such as India and Korea. The high compliance cost is associated with documentary requirements for customs clearance. On average, Pakistan requires 400 hours while India and Korea require 270 and 196 hours, respectively (Table: 1). Similarly, the time taken for the customs clearance process and documentary compliance in case of imports is 12 times longer than in UAE. The indirect cost associated with uncertainty and delays affects customer choices. On the other hand, poor track and trace consignments, custom clearance, inexpedient schedule, transport-related infrastructure are bottlenecks that keep the industry from meeting its actual potential. According to the Ministry of Maritime Affairs, Pakistan can raise its share in transhipment to 200,000 TEU’s, which can be further increased by removing procedural inefficiencies.

It is paradoxical to note that Pakistan has a small shipping sector despite having trade of over $70 billion. Ministry of Maritime affairs is well cognizant of the true potential and possesses the will to transform the sector into a profitable economy sector. It has sought a phased policy to transform and leverage the actual potential of the sector. The only need is to highlight the weaknesses in the prevalent policies and overcome mistakes being made in shipping practices. A large number of vessels owned by private Pakistani owners operate under the Flag of Convenience (FOC). There is a need to bring in all long-term imports under Freight on Board (FOB) basis, mandating it for Pakistani Flag vessels to lift it. Proper checks and balances should be enforced to avoid delays under this system. The Ethiopian model offers a lot to learn from it.

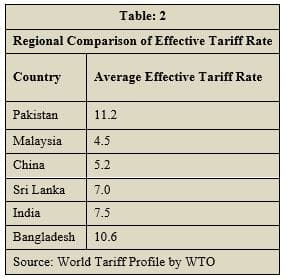

Pakistan adopted a protectionism policy while many countries like Turkey and Chile liberalised their economies and saw sustainable growth and their manufacturing sector developed. Consequently, local manufacturers neither developed nor upgraded their technology to cope with modern world markets. The tariff rate followed by Pakistan is much higher than other countries in the region, as depicted in Table: 2. Sri Lanka and Malaysia have a meager effective tariff rate of 7.0 and 4.5, respectively, whereas Pakistan follows an average effective tariff rate of 11.2. The policymakers should consider economic liberalisation policy to boost trade, and the involvement of maritime needs particular focus to execute it effectively.

Pakistan needs to allocate more funds for infrastructure development, up-gradation, and diversification of its fleet. However, the Maritime Affairs division budget was reduced to PKRs. 2.6 billion in 2021, which was PKRs. 3.6 billion in 2020. Reduction in the budget for maritime division may not directly impact the industry, but it hampered the infrastructure development efforts. More autonomy should be afforded to PNSC as well as other private entities in order to encourage investment and competition.

Pakistan has a large EEZ, and long coast, and this sector is vital for economic growth, employment generation, and food supply. There is a shortage of trained and skilled professionals domestically and internationally due to the ever-expanding shipping market. Pakistan can train and produce skilled professionals to meet the demand of domestic maritime activity and supply of human capital to the international market.

BOAT AND SHIPPING INDUSTRY IN PAKISTAN

The shipping industry holds paramount importance in any economy in today’s globalised world as 80 percent of world trade is carried out through the sea. Over 90 percent of Pakistan’s trade by volume is through the sea.

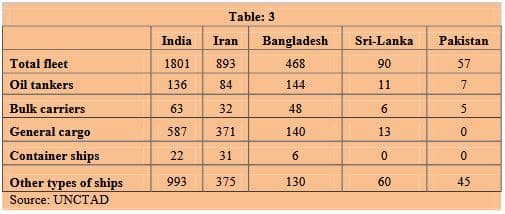

The shipping sector of Pakistan is governed by several organisations under both international law and a dedicated national shipping policy. The Ministry of Maritime affairs acts as the supreme authority to regulate most of the maritime sector of Pakistan. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation (PNSC) is the largest and the only Pakistani flag shipping company in Pakistan lifting only 10-11 percent of Pakistani cargo (Yousuf and Ali 2020). Worldwide, 70,094 ships are registered, out of which the USA operates 3000 registered ships. As of 2021 in the Southern Asia region, (Table: 3) depicts the fleet size of countries in the region. Pakistan possesses seven oil tankers, five bulk carriers, and a total fleet of 57 ships, which is the lowest number compared with other regional countries. India has a total fleet of 1801, Bangladesh 468, Sri Lanka 90, and Iran, despite long-standing international sanctions, maintains 893 ships. Not just that, Pakistan does not possess a single general cargo or containership. The regional countries comparison calls out the vulnerable position of Pakistan’s fleet size. The concerned authority must look forward to acquiring oil tankers and bulk carrier ships in the first phase, as Pakistan depends on oil import.

According to PNSC 2018 import data, 916 import shipments were made, including 341 shipments of oil. Similarly, according to port’s import data sources, 840 shipments were made that including 13 shipments of jet fuel. (NIMA).

According to PNSC 2018 import data, 916 import shipments were made, including 341 shipments of oil. Similarly, according to port’s import data sources, 840 shipments were made that including 13 shipments of jet fuel. (NIMA).

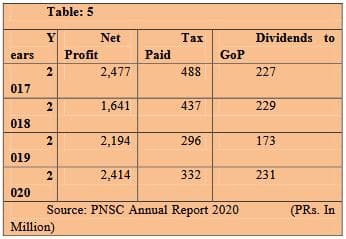

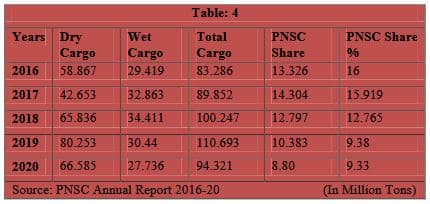

The amount of trade through sea has been increasing every year but the share of PNSC is decreasing instead of going up (Table: 4). In 2018, the total seaborne trade of Pakistan was 100.247 million tons, and PNSC was trading about 12.76 percent of it. According to official sources, PNSC imports only 26 percent of liquid and only 3 percent of dry bulk cargo of the country, while the rest is imported through foreign vessels. Similarly, in 2020 total seaborne trade of Pakistan was 94.321 million tons, where the PNSC share was 9.33 percent. This costs Pakistan a whopping 5 billion USD freight charges annually that is paid to foreign vessels. In 2020, PNSC earned a net profit of about PKRs. 2,414 million and paid PKRs. 332 million worth of taxes and PKRs. 231 million in dividends to the government, an increase of 10 percent compared to last year (Table: 5). In some Flag of convenience countries, an overwhelming majority of the World’s ships are registered due to easy processes, no taxes and no questions about the source of investments.

Despite giving incentives through federal tax exemption and lowering the tax to US$ 0.75 per Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT), the private sector is reluctant to get the benefit. The investors’ confidence was shaken by ill-thought out of private shipping lines in the 70’s and safe investment avenues available in Tax-free havens. On the other hand, the Merchant Marine Department (MMD) is behind time with unskilled staff that cannot handle the modern demands of the shipping sector and registration maintenance (NIMA). Whereas the leading flag of convenience countries provide services and can register and de-register ships in 24hrs.

Despite giving incentives through federal tax exemption and lowering the tax to US$ 0.75 per Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT), the private sector is reluctant to get the benefit. The investors’ confidence was shaken by ill-thought out of private shipping lines in the 70’s and safe investment avenues available in Tax-free havens. On the other hand, the Merchant Marine Department (MMD) is behind time with unskilled staff that cannot handle the modern demands of the shipping sector and registration maintenance (NIMA). Whereas the leading flag of convenience countries provide services and can register and de-register ships in 24hrs.

The domestic boat industry of Pakistan, requires urgent government support before the traditional artisans and boat makers become extinct. Due to official apathy, traditional boat building is moving outside Pakistan. At one time, Pakistan was the largest builder of Dhows in the region. The informal sector involved in the boat-making industry is running side by side. According to a report, it employs about 3,500 skilled labourers. The workers are expert enough to build small or large boats without drawing and sketches, and most of the workers earn a daily wage of about $14.

It is time to take upon the cross-disciplinary approaches to deal with new world challenges and tradeoffs. Government intervention will be especially welcomed in introducing incentive schemes and facilitation services for the registration of boats and the development of boat engines that are efficient and durable in extreme weather conditions. Government intervention is also required in record-keeping and pricing of water transport services in Pakistan. State Bank of Pakistan has allowed a long-term finance facility (LTFF) under Merchant Marine Policy 2001 that will allow investors long-term borrowing at 3 percent to acquire floating vessels, tug boats, cargo vessels, and fishing boats. Currently, seafood export is US$ 450 million, but fishing stocks are depleting fast, and fishing is becoming unsustainable. The country needs to invest heavily in Aquaculture to boost the fisheries sector and increase export seafood up to USD$ 2 billion annually while concurrently increasing the country’s food security.

TOURISM—GOING BLUE

The tourism industry is one of the world’s fastest-growing and is closely linked to the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of many countries around the globe. The role of maritime tourism is well integrated into contemporary economies that the economic impact is relevant even to the less important countries in terms of tourism-related activities (Bunghez 2016). The tourism economy represents 10.4 percent of the global GDP, which makes about 8.8 trillion dollars. About one out of every ten jobs is created by tourism-related industry. Tourism is one of the top five earning industries and a key source in generating foreign exchange in half of the developing nations. Small islands and developing countries have vast untapped potential regarding ocean-related tourism to create job opportunities and earn foreign exchange. Sustainable tourism takes account of the social, environmental, and future economic impacts while addressing the needs of visitors and host communities. The agenda for 2030 for Sustainable Development SDG target aims to implement policies to promote sustainable tourism to promote local product, culture and create job opportunities. Pakistan has immense Maritime tourism potential with a long coastline of 990 Kilometres which is blessed with diversified natural, religious, and cultural tourism resources. In 1989, Pakistan gave tourism an industry status. The federal government established a Beach Development Authority under Pakistan National Tourism Policy 1990 (NTP 1990) to develop beaches and encourage water sports activities. The long-term policy was given under the Ministry of Culture, sports, youth affairs, and tourism to collaborate with provincial governments of Sindh and Balochistan provinces to promote water sport activities and tourism. However, maritime tourism is undeveloped due to political instability, lack of coordination among tourism authorities, poor governance, and security concerns (Ahmed and Mahmood 2017). NTP 1990 is no more effective after the 18th amendment in the constitution as tourism is now a devolved subject.

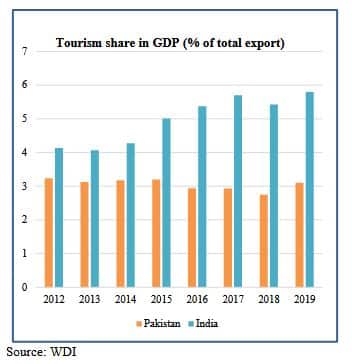

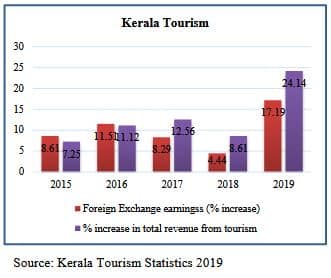

Boating tourism, marine sports activities, beach development, and other aquatic environment are core sectors, and all other recreational activities come under marine-related tourism. When we compare the share of tourism in the GDP of Pakistan with the neighbouring country India, it shows that Pakistan is lagging in developing the tourism sector. For instance, consider an example of Kerala that has about 600km Arabian Sea shoreline and has been developed as a tourism hotspot. Over the years, tourism in Kerala has grown significantly to earn foreign exchange, revenue increase, and living standards of people associated with tourism activities. In 2019, a 17.19 percent increase in foreign exchange and 24.14 percent increase in revenue generated from tourism (Direct and indirect) was recorded in Kerala. The current government of Pakistan has paid attention to developing the tourism sector. However, government is more focused on land-based tourism and is neglecting the capacity of marine tourism. The availability of vast resources is a blessing and must be properly developed as it can significantly raise the standards of coastal communities used by human beings. Pakistan must develop a vast spectrum of marine tourism activities like harbour cruises, recreational fishing, maritime museums, sailing yachting, beach activities, windsurfing, scuba diving, snorkelling, sea kayaking, and many more. Investors should be motivated with incentives like tax reliefs, high-profit expectations, ease of documentation process, and security guarantee. On the other hand, awareness and a friendly environment should be provided to local communities and visitors. The development of international tourism will pave the way to revenue generation and foreign exchange reserves.

Boating tourism, marine sports activities, beach development, and other aquatic environment are core sectors, and all other recreational activities come under marine-related tourism. When we compare the share of tourism in the GDP of Pakistan with the neighbouring country India, it shows that Pakistan is lagging in developing the tourism sector. For instance, consider an example of Kerala that has about 600km Arabian Sea shoreline and has been developed as a tourism hotspot. Over the years, tourism in Kerala has grown significantly to earn foreign exchange, revenue increase, and living standards of people associated with tourism activities. In 2019, a 17.19 percent increase in foreign exchange and 24.14 percent increase in revenue generated from tourism (Direct and indirect) was recorded in Kerala. The current government of Pakistan has paid attention to developing the tourism sector. However, government is more focused on land-based tourism and is neglecting the capacity of marine tourism. The availability of vast resources is a blessing and must be properly developed as it can significantly raise the standards of coastal communities used by human beings. Pakistan must develop a vast spectrum of marine tourism activities like harbour cruises, recreational fishing, maritime museums, sailing yachting, beach activities, windsurfing, scuba diving, snorkelling, sea kayaking, and many more. Investors should be motivated with incentives like tax reliefs, high-profit expectations, ease of documentation process, and security guarantee. On the other hand, awareness and a friendly environment should be provided to local communities and visitors. The development of international tourism will pave the way to revenue generation and foreign exchange reserves.

CHALLENGES AND WAY FORWARD

The present government is revisiting its approach for the improvement in the marine sector of Pakistan. Primarily, the lives of people working in the marine sector need improvement and special support from the government. Studies have shown that the majority of problems faced by fishermen can be solved through minor interventions. Lack of education among these communities has kept them from modern technologies and systems.

Institutional constraints have restricted Pakistan’s potential gains from the “Blue Economy”. It is important to have the institutional capacity for dealing with Blue Economy. What seemed like a distant dream is, fortunately, converging towards reality due to the present government’s efforts. In Pakistan, the local boat industry is still functioning without government support and is losing its competitiveness to other players. (Moazzam 2012) added that most registered boats have dual registration for Pakistan and Iran, which eventually poses a security threat. In Karachi, small boats are used for tourism purposes, local transport purposes, and larger vessels are in the business of to carry cargo in the region.

Institutional constraints have restricted Pakistan’s potential gains from the “Blue Economy”. It is important to have the institutional capacity for dealing with Blue Economy. What seemed like a distant dream is, fortunately, converging towards reality due to the present government’s efforts. In Pakistan, the local boat industry is still functioning without government support and is losing its competitiveness to other players. (Moazzam 2012) added that most registered boats have dual registration for Pakistan and Iran, which eventually poses a security threat. In Karachi, small boats are used for tourism purposes, local transport purposes, and larger vessels are in the business of to carry cargo in the region.

ACTION POINTS- THE WAY FORWARD

The following action plan for policymakers is based on the observation of internationally acknowledged practices. The study advocates to:

- Establish a network of researchers, industry stakeholders, government personnel, and media outlets to generate and disseminate awareness and knowledge regarding the scope and potential of blue resources. Information campaigns and mainstreaming and dissemination of the knowledge created by researchers for broader awareness and insights into the field will be beneficial.

- A complete survey and manpower audit of the Mercantile Marine Department (MMD) is required to identify the shortcomings, capacity, and needed up-gradation to fulfil its functions.

- Conduct a dedicated and full-fledged survey of Pakistan’s maritime zones to ascertain the nature, type, and extent of resources to better understand Pakistan’s blue potential.

- Strategise for a conducive environment for foreign and local investors to channel investments into the maritime sectors.

- Review procedural inefficiencies and introduce reforms for fostering investor confidence and improving prospects of business in the blue economy.

- Putting in place consistent long-term policies that are dynamic rather than static.

- Formulate an exclusive National Blue Growth Policy with clearly defined goals and realistically set targets to be achieved within a reasonable time. Greater coordination and consultations among academia, government, and other stakeholders are the key to achieving consensus in decision-making.

- Eliminate subsidies for bringing in competitiveness.

- Invest in R&D and forge partnerships with international research groups to keep pace with the current international practices.

CONCLUSION

Pakistan has a unique geostrategic location that offers opportunities and challenges as well. Geographical location, investment, and timely implemented policies are important in sea trade and ports development. For instance, the Middle Eastern countries incorporate about 3 percent of world GDP and handle about 20 percent of seaborne trade. Further, transhipment accounts for 53 percent. Pakistan can serve as a viable and most effective economic transit route to land-locked Central Asia and neighbouring countries. China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) can spur economic activity in Pakistan and regional countries through roads and railway networks, whereas ports at the Arabian Sea will provide global connectivity. The Marine economy is one of the main pillars of economic structure, which needs a proper regulatory authority to monitor and evaluate it. It will play a critical role in the economic growth of Pakistan. This sector is facing numerous challenges like lack of institutional capacity, poor governance, and investment. The sector needs well-thought-out actions from the government including ease of business processes. The revenue from the sea routes transport system can be improved. The government has to play an important role to enhance ships fleet and increase the share of GDP. In addition, maritime tourism can generate $1-2 Billion annually through domestic/international tourism and employ coastal community people.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, R. and K. Mahmood (2017). Tourism potential and constraints: an analysis of tourist spatial attributes in Pakistan. Pakistan Perspectives, 22(2).

Bunghez, C. L. (2016). The importance of tourism to a destination’s economy. Journal of Eastern Europe Research in Business & Economics, 1–9.

Doyle, T. (2018). Blue economy and the Indian Ocean Rim. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region. Accessed from https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1421450.

FAO Statistics, Country Profile, Pakistan. http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/PAK/en

Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles, The Islamic Republic of Pakistan http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/PAK/en

Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles. Pakistan (2009). Country Profile Fact Sheets. In: FAO Fisheries Division [online]. Rome. Updated 1 December 2017. [Cited 22 December 2020]. http://www.fao.org/fishery/

Moazzam, M. (2012). Status report on bycatch of tuna gillnet operations in Pakistan. IOTC 8thsession of the Working party on ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB).

Nasir, M., Faraz, N., & Anwar, S. (2020). Doing taxes better: Simply, open and grow economy”. (PIDE Policy Viewpoint No. 17) https://file.pide.org.pk/pdf/Policy-Viewpoint-17.pdf.

National Institute of Oceanography, Govt. of Pakistan. http://www.niopk.gov.pk/introduction.html #:~:text=The%20Exclusive%20Economic%20Zone%20(EEZ,30%25%20of%20the%20land%20area.

Nazir, K., Yongtong, M., Kalhoro, M. A., Memon, K. H., Mohsin, M., & Kartika, S. (2015). A preliminary study on fisheries economy of Pakistan: plan of actions for fisheries management in Pakistan. Canadian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 3(01), 7–17.

Pakistan Merchant Marine Policy (2001). Amendment 2019. Ministry of Maritime Affairs, Government of Pakistan.

Pakistan’s shipping sector potential. https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/pakistan-shipping-sectors-potential/

Pastner, S. (1978). Baloch fishermen in Pakistan. Asian Affairs, 9(2), 161–167.

Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Diez, S. M., Roberts, J., & Singh, A. (2016). Toward a blue economy: A promise for sustainable growth in the Caribbean; An overview. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

PEMSEA (2018). Policy brief for the blue economy—Sustainable fishing and aquaculture. Retrieved from http://pemsea.org/publications/reports/policy-brief-blue-economy-sustainable-fishing-and-aquaculture

Rahman, A. and Salman, A. (2013). A district level climate change vulnerability index of Pakistan. PIDE, Islamabad, Centre for Environmental Economics and Climate Change (CEECC) Working Paper (5).

Rashid, A. (2017). Water as blue economy for sustainable growth in Pakistan. Journal of Basic & Applied Sciences, 248–258. NIMSA Policy Paper.

Roy, A. (2019) Blue economy in the Indian Ocean: Governance perspectives for sustainable development in the region. (ORF Occasional Paper No. 181). Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.orfonline.org/research/blue-economy-in-the-indian-ocean-governance-perspectives-for-sustainable-development-in-the-region-47449/

Rustomjee, C. (2016). Financing the Blue Economy in Small States. (Policy Brief) Retrieved from https://www. cigionline.org/sites/default/files/pb_no78_web.pdf.

Salman, A., & Abbasi, J. (2019). Towards blue growth: A Sustainable Ocean-led Development Paradigm (SODP) for Pakistan. Maritime Study Forum, Islamabad.

Statistics, P. B. O. (2019). Pakistan Statistical Year Book. Karachi: Division, Government of Pakistan, PBS, Reproduction, and Printing Unit.

Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. “Sustainable Development Goal 14”, https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal14

The Research Collective (2017). Occupation of the coast – Blue economy in India. Retrieved from https://in.boell.org/en/2018/04/26/occupation-coast-blue-economy-india.

UNDP (2018). Leveraging the Blue Economy for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth. (Policy Brief) UNDP, Kenya. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/kenya/docs/UNDP%20Reports/Policy%20Brief%20%202018%20-%206-%20%20Blue%20Economy%20for%20Inclusive%20and%20Sustainable%20Growth.pdf.

World Bank and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2017). The potential of the blue economy: increasing long-term benefits of the sustainable use of marine resources for small island developing states and coastal least developed countries. World Bank, Washington DC. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment. un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=2446&menu=1515

Yousuf, M. A. and Ali, T. (2020). Downfall of local shipping industry of Pakistan—A case study of Pakistan National Shipping Corporation. Journal of Marketing & Management, 11(1).